Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: Ghosts of Berlin

April 18, 2023Today Courtney and I spent the day on a historical walking tour of Berlin through the city’s inauspicious beginnings, through Prussian imperialism and the raucous years of the Weimar Republic, the countless tragedies of the Second World War, the intrigue of the Cold War, the new dawn of German Reunification, to today’s vibrant & cosmopolitan city.

We visited the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag building, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, the site of Adolf Hitler’s Führerbunker, the Topography of Terror Museum, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the Soviet War Memorial in Treptow, and many other sites steeped in the complicated history that accompanies cities of empire.

Brian Ladd in The Ghosts of Berlin writes:

Berlin is a haunted city. By the middle of this [20th] century, people living in Berlin could look back on a host of troubles: the last ruler of an ancient dynasty driven to abdication and exile by a lost war; a new republic that failed; a dictatorship that ruled by terror; and that terror unleashed on the rest of Europe, bring retribution in the form of devastation, defeat, and division. Now that division, and the regime the ruled East Berlin, are also memories. But memories can be a potent force. There are, of course, Berliners who would like to forget. They think they hear far too much about Hitler and vanished Jews and alleged crimes of their parents and grandparents- not to mention Erich Honecker and the Stasi and their own previous lives. Probably most Germans and most Berliners feel this way, but at every step they find they must defend their wish to forget against fellow citizens who insist on remembering. The calls for remembrance- and the calls for silence and forgetting—make all the silence and all the forgetting impossible, and they also make remembrance difficult.

But memories are often tied to place. It’s why we protect and preserve the Old Session House at Derry. It’s why we preserve and maintain places like Williamsburg, Virginia and Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Buildings and places have stories to tell, like the fields and hills around Gettysburg.

Courtney and I will visit museums that tell the stories of those names many of us have heard of: Hitler, Frederick the Great, Otto Von Bismarck, and Kaiser Wilhelm, but will also tell the stories of the average citizen’s role and plight through the long history of what is now called Germany. But we wanted to start with the setting, the city, and let it tell its own stories through its buildings, ruins, and monuments.

Ladd writes, “Each era in Berlin’s history has left its monuments—visible and remembered, planned and accidental.” We walked journeyed through the city, and in doing so through an evolution of identities: a royal residence, an industrial and imperial powerhouse, a Nazi capital, a Cold War battleground, and a newly reunified capital. Each of these identities tells a story through the monuments, remnants, and still towering edifices.

One of the first things we saw was the Brandenburg Gate, which was inspired by the Propylaea entrance to the Acropolis in Athens. The ceremonial entrance into Berlin, the capital of the Kingdom of Prussia at the time, was erected by the Prussian Hohenzollern monarchy in 1791 as a “Peace Gate.” It is the only entrance remaining of the 18 that once surrounded Old Berlin. Use of this gateway was strictly regulated, with commoners only permitted to use the outer two lanes either side and the center reserved for Royalty, until the abdication of William II, the last German Emperor, in 1918.

On top of the gate is a statue known as the “Quadriga,” which depicts the goddess of victory driving a chariot pulled by four horses. It has endured several changes since it was first installed in 1791. The statue remained in place for just over a decade until Napoleon Bonaparte and his Grand Army took the city without firing a shot. After occupying Berlin that fall and triumphantly marching beneath the arches of the Gate, Napoleon ordered the Quadriga dismantled and shipped back to Paris.

While Napoleon’s empire started to crumble, the statue appears to have been forgotten because it languished in storage until 1814. When Paris was captured by Prussian soldiers following Napoleon’s defeat, the Quadriga was returned to Berlin. It was re-installed atop the Brandenburg Gate, but an iron cross was added as a symbol of Prussia’s military victory over France. The cross was later removed during the Communist era, and only permanently restored in 1990 during the unification of Germany. The current statue is a re-creation of the original, since it was heavily damaged in the Battle of Berlin.

It’s interesting how we sometimes change our national symbols in response to current events, but then historical memory becomes that it has always been that way. For the longest time I didn’t realize that US money didn’t always have “In God We Trust” on it. We add things and change things on our symbols all the time for various reasons. For instance, the Confederate flag was added to the statehouse in South Carolina in 1962 in what was clearly a direct response to the civil rights movement, but when I was growing up, people talked about it as some long-standing important tradition. When you look back at the history of a lot of memorials that are considered “sacred with a long history,” you realize that the reasons they were put up was often not so pure.

One unique experience was climbing the glass cupola of the Reichstag building, which offered spectacular views of the city. After the building was badly damaged in WWII, it needed to be rebuilt and it needed to be a new kind of symbol for the city. The seat of government is now transparent and light shines onto the legislative body below. The public is able to ascend symbolically above the heads of their representatives in the chamber and keep watch of them and how they govern. There was actually debate whether the capital of Germany should still be Berlin, but in a narrow vote it was decided that Berlin was the capital and they needed to reckon with the past while also turning the page to a new chapter where it all began. It was interesting to learn the history of the area and what Hitler had planned to create there had he won the war and remained in power.

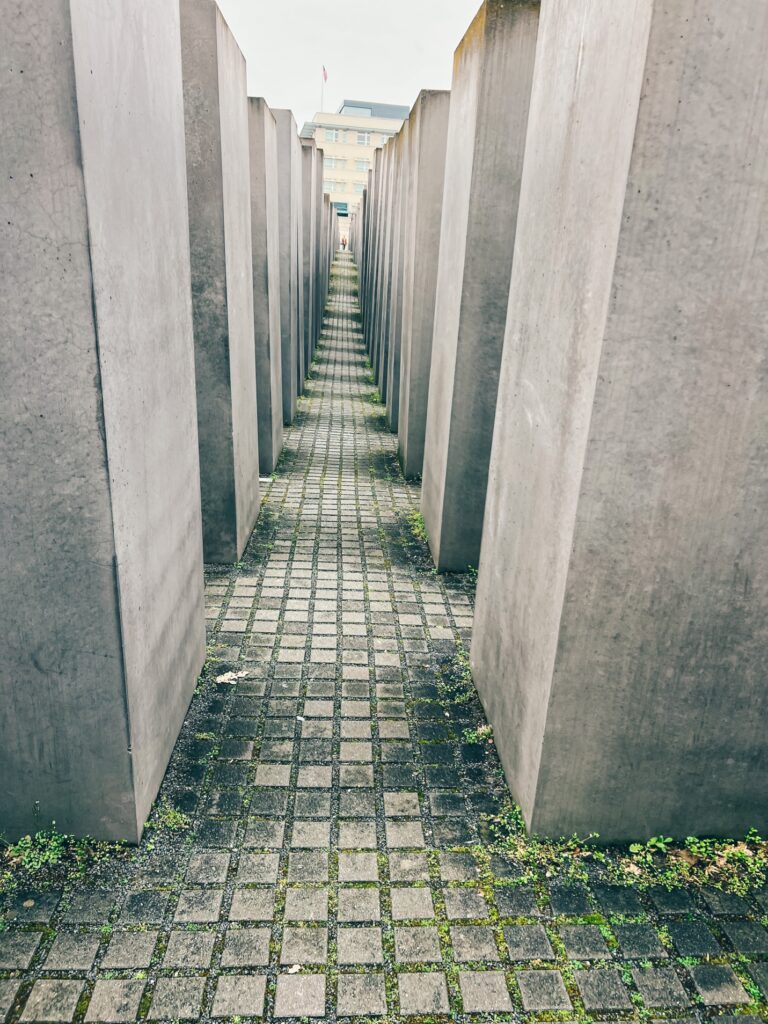

One of the most profound places we visited was the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Holocaust Memorial). The Memorial consists of massive stone blocks arranged on a 204,440 square foot plot of land between East and West Berlin. The 2,711 rectangular concrete slabs (stele) placed on a sloping stretch of land have similar lengths and widths, but various heights.

The use of the stele is an ancient architectural tool to honor the dead. The stone marker, to a smaller extent, is used even today. Ancient stelae often have inscriptions; but the architect chose not to inscribe the stelae of the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. Perhaps the strength of the design is in its mass of anonymity. In this monument there is no goal, no end, no working one’s way in or out; you’re just in it and there are no answers. The memorial is not supposed to be easy or provide answers. There’s no central point of remembrance; it surrounds you while at the same time giving you space to confront the past and your present feelings in your own way.

Walking through the memorial was a bit disorienting, like a maze, as if you’re trying to find the right emotions to feel but there’s no end or goal of the maze or right emotion to ever find. The ground is not even, it undulates, so you never feel fully steady, but you always have to walk uphill to get out. It felt cold, but I think that’s part of the point. It offered no comfort and maybe that isn’t what is needed. Sometimes we have to deal with the cold, painful, atrocities of our world just as victims of those atrocities have had to do for millennia.

There are plenty of critics of the design and form of the Memorial, but Susan Neiman says, “A nation that erects a monument of shame for the evils of its history in its most prominent space is a nation that is not afraid to confront its own failures.”

I like that. I think as individuals we are often afraid to confront our own failures, but I’ve found it’s freeing. I often learn more from my failures than anything else. If I hide from my failures, I can never grow from them or live out my true identity because I’ll always be hiding something.

After the visit, I realized I need to go to Montgomery, Alabama and visit the Memorial for Peace and Justice. Stevenson’s inspiration was the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. The six-acre site contains 801 six-foot monuments constructed of corten steel to symbolize their brutal deaths, museum officials say. The names of the victims are carved into the steel columns that dangle from beams, much like the lynched bodies of men, women and children dangled from trees.

I imagine weaving through the 801 steel columns would be a similar experience to walking here in Berlin among the concrete stele. There’s no one way to feel. I can’t explain all my feelings, and honestly, it’s not about what you feel: it’s about confronting a truth and a past we shouldn’t seek to escape from. These are not tombs to be whitewashed or buried. They are for us to confront, consider, confess, and perhaps convert our way of thinking and being in this world together.

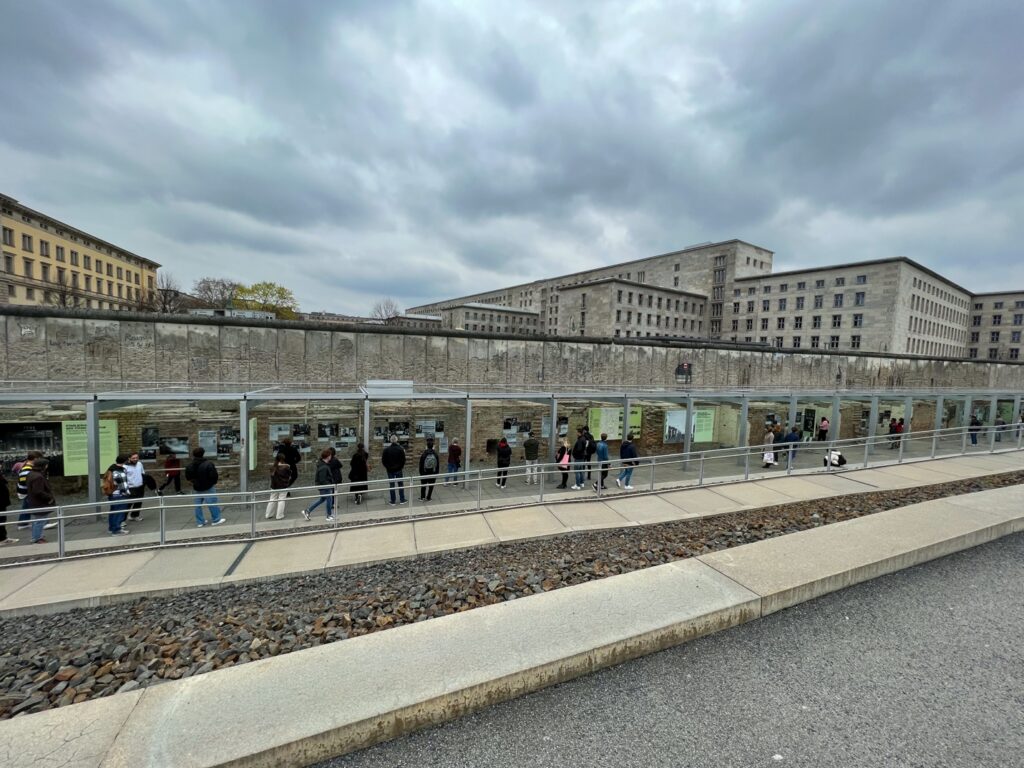

We also visited a site called “The Topography of Terror” that was built upon the old side of the SS and Gestapo headquarters. The museum helps visitors understand and unmask the Nazi ideology and contemplate a system that normalized cruelty and rewarded ruthlessness. This is the kind of museum that Neiman talks about when she speaks of the need to “work off the past.” It wasn’t until the late 80s that work began on the site to document what happened there. It is now a memorial and permanent exhibition showing the crimes of Nazism.

I marvel at how the Topography of Terror extends its focus beyond that of other museums around the world that aim to preserve the memory of the victims of Nazi persecution and tell their stories, where National Socialist doctrine would otherwise want for these things to be forgotten. Here the spotlight is on the perpetrators, their identities, their actions, and the justifications they would give for their crimes. Most of those crimes would remain unpunished for decades after with many of the perpetrators being allow to escape justice entirely.

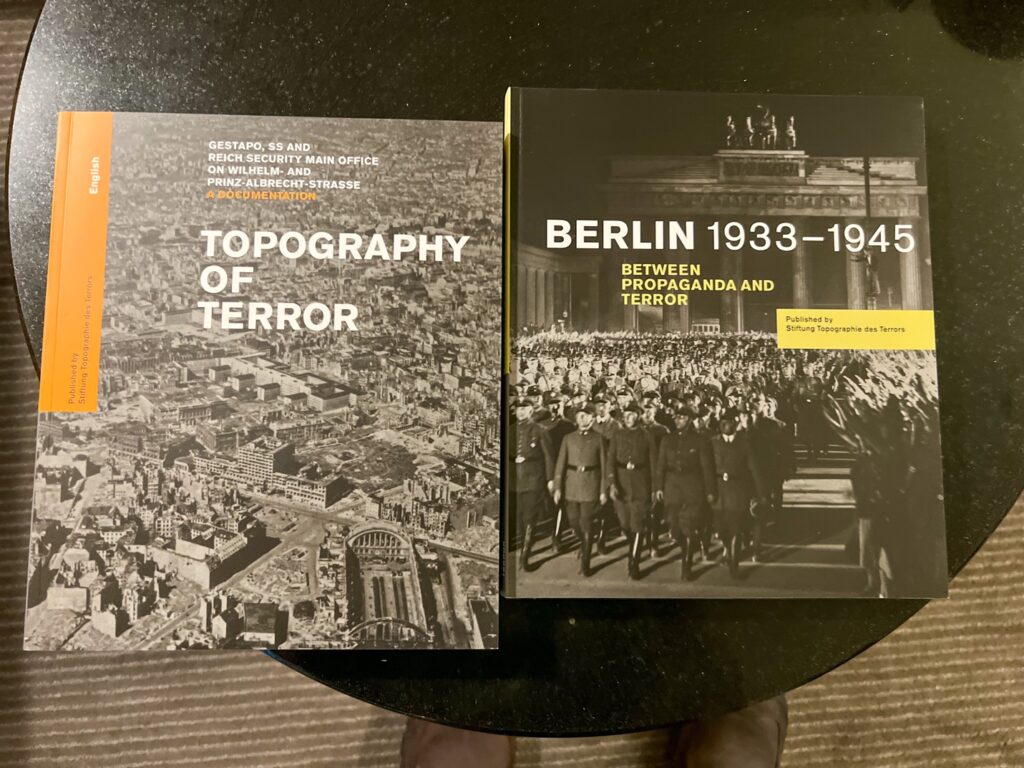

We bought two thick books there that go over everything in the museum so we’ll have time to really absorb more of it. There’s just so much and it’s shocking, depressing, familiar, believable, and unbelievable all that the same time.

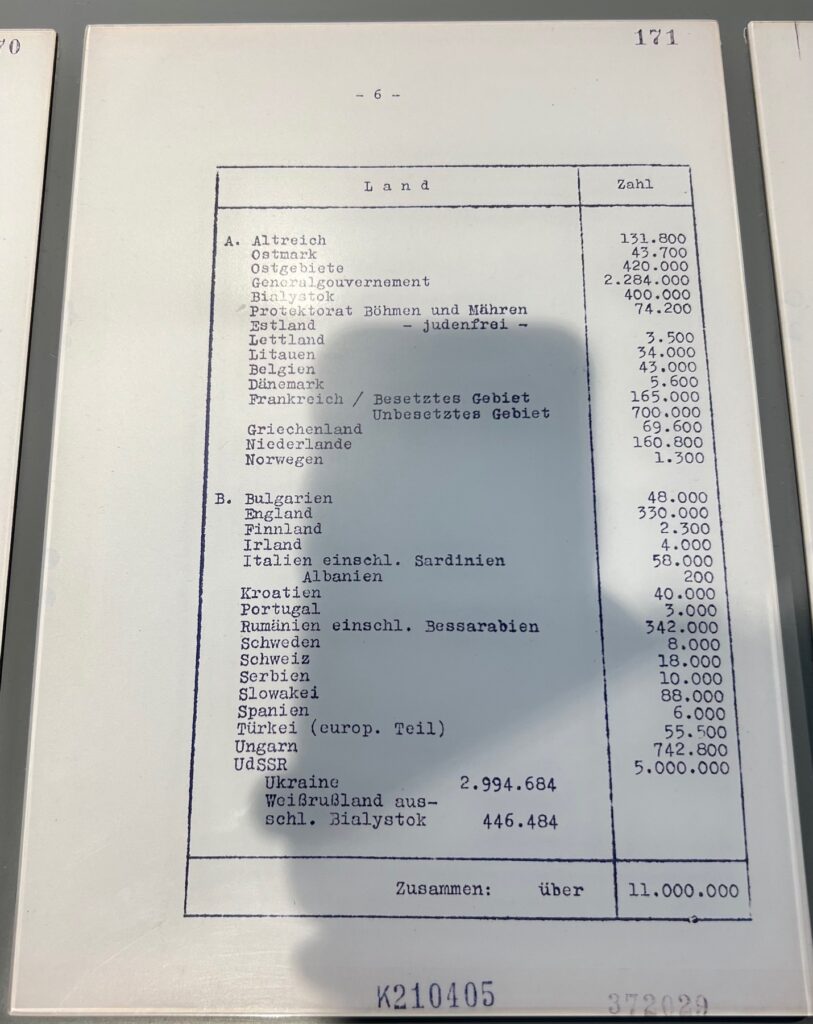

One of the things that really hit me was papers from the meeting when the “Final Solution” to the Jewish question was discussed. There was a memo with the countries in Europe Germany controlled already and those they did not, but it listed how many Jews were in each country and provided a total number of Jewish people in Europe they planned to murder.

I’ve been to the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem and I’ve been to exhibits that remember the victims of tragedies and systemic acts of injustice, but I can’t remember ever visiting a place that focused on those who did the wrong with names and pictures and evidence of their crimes.

The Topography of Terror was a unique opportunity to confront the cruel actions of these men and women, right in the place where it happened, but in a way that transformed a location that once enabled these crimes into a place to engage with the history so that we might do better and repair what has been broken.

Do you think the US should have a similar memorial somewhere? If so, where and what should it memorialize for us and the rest of the world to remember?

We also visited the Soviet War Memorial in Treptow Park. It’s a massive memorial that is also a cemetery for 7,000 Russian soldiers. A round arched portal entrance guides you into the symmetrically laid-out memorial. The paths meet at the forecourt where you will see a sculpture, Mother Russia: a woman grieving for her fallen sons.

An avenue of weeping willows takes you past two flags carved from red granite. Behind them, five lawns and eight sarcophagi are arranged. The lawns symbolize the communal graves. The actual cemetery of the soldiers of the Red Army is behind the sarcophagi, under the plane trees.

The centerpiece is the mausoleum on a hill, topped by the statue of a Soviet soldier, carrying a child in one arm and resting his sword on a shattered swastika. The soldier’s sword is down, symbolizing an end to the vengeance needed for the Battle of Stalingrad. There’s a memorial statue there of Mother Russia holding a sword up in the direction of Berlin. It’s a beautiful and moving memorial that tells the story of the German invasion of Russia through the Battle of Stalingrad which led to the Red Army invading Berlin, told through pictures carved into granite blocks.

There are memorials throughout Berlin: some big and some small. Some are erected by nations like the Soviet Memorial (there are actually three in Berlin), others are placed by individuals like the Stumbling Stones, some buildings are memorials like the remains of the Kaiser Wilhelm church, and some memorials include pictures and names of victims. Each tells a story and calls us to remember and to learn.

Is there a memorial to the victims of the Conestoga Massacre in Lancaster? I haven’t read about one. There is a very high probability that members of Derry Church participated in that. While there is no evidence John Elder participated, he most likely knew about it and didn’t stop it. He helped create the environment for it to happen. The situation and context that led to the massacre is complicated and nuanced, but it should not have happened. Courtney and I wonder if a memorial should be created with their names, lest they are forgotten? Derry, and its community, had a role in it one way or another. How can and should we reckon with the past? As we approach our 300th anniversary, should we only lift up the easy and triumphant parts of our heritage, or can we confront the shadow parts of our past in order to live a better future?

There is a smaller, less well-known, memorial that is just across the street from our hotel in a little park. The “Block of Women” commemorates the site of a protest/rebellion by a large group of German women in 1943.

In February 1943, the SS and Gestapo detained around 8,000 Jewish citizens in Berlin including about 2,000 Jewish men who were partners in mixed marriages. The authorities separated these men from the rest of the prisoners and held them in the building that once held the Jewish Welfare Administration at 2-4 Rosenstrasse.

Once the women found out where their husbands were being held, they gathered together and demanded to speak with their loved ones, requesting their release. For a week, over 600 women protested daily in Rosenstrasse. The women refused to leave until the Nazi authorities released the men of the families even after threats from the SS.

The Nazis knew that German morale would suffer if they murdered hundreds of unarmed women in the streets of Berlin. On 5th March 1943, trucks laden with machine guns arrived in Rosenstrasse but again the women would not back down. The following night, Joseph Goebbels ordered the release of all the men in 2-4 Rosenstrasse.

The inscription on the memorial reads:

THE POWER OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE AND THE POWER OF LOVE

OVERCAME THE VIOLENCE OF THE DICTATORSHIP

WOMEN STOOD HERE

DEFYING DEATH

GIVE US OUR MEN BACK

JEWISH MEN WERE FREE

This memorial is apparently one of Susan Neiman’s favorites. She says what is tragic is not that these heroines’ names are unremembered, but that no one followed their example. She says, “What stopped others from doing so was not only the fear of Nazi terror, but something else as well: the belief that heroic action is futile, and usually ends in death besides.”

The depravity of humanity never ceases to amaze me: the horrible things we can do to each other. We are seeing such horrific acts out of Ukraine now: torture, beheadings, mass graves. The Holocaust was certainly such an evil time. But the courage and resilience of humans amaze me, too. Those stories, like the one told by the Block of Women, give me hope. I wish we told those stories more in the US, because we have so many of them.

Bryan Stevenson suggests that more US (especially Southern) buildings and streets be renamed after people in these stories of hope and courage in the face of injustice. If those names and stories were commemorated, we could turn from shame to pride. Stevenson says, “We can actually claim a heritage rooted in courage, and defiance of doing what is easy, and preferring what is right. We can make that the norm we want to celebrate as our Southern [US] history and heritage and culture.”

The US is filled with unknown heroes, but it’s not always easy to find them. They are memorialized in small out-of-the-way parks and buildings like the Block of Women in Berlin. There’s one to a man named James Reeb in Princeton, NJ. Do you know his story? There are heroes if we would look to them. Susan Neiman writes, “Heroes close the gap between the ought and the is. They show that it’s not only possible to use our freedom to stand against injustice, but that some folks have actually done so.”

We need those heroes and we need those stories for a time such as this. We don’t only have to memorialize the tragedies and atrocities and victims. We can memorialize the heroic and the hopeful, because that, too, is an important part of our story, the narrative that binds us together.

Read more Berlin travel notes:

Learning from the Germans (4/17/23)

Why Berlin? (4/16/23)