Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Langa Township

October 9, 2022

I visited Langa township in Cape Town with a local resident who showed me around, introduced me to people, and told me stories. I entered into small rooms that served as a home for a whole family, saw the businesses run out of small shipping containers, and the old courthouse pass office that regulated the movements of the residents.

I’ve heard about the townships in South Africa since high school when I read Cry, the Beloved Country, but I haven’t taken the time to really understand them or why such disparity exists in different parts of the same city. But it’s a reality in every city from Cape Town to Chicago.

I admit feeling a little odd touring a township. It feels a bit like poverty tourism, which is uncomfortable. I felt a little better being with a resident and learning from him, but there’s still a voyeuristic feeling to it. I wanted to learn and be more aware of Langa’s history and present. I wanted to see them and not just skip over these important areas of Cape Town in favor of the typical tourist locations. At times it was upsetting to see how some people had to live, and yet there was joy in the community. I saw little boys playing with cars they made out of milk cartons and caps. I saw women preparing sheep heads to sell for meat, and women braiding each other’s hair in small communal spaces. My guide, Ludumo, told me how everything was really communal there. People share cooking spaces, bath houses, lines for drying clothes and everything else. They work together and rely on each other because they need to. There’s no other way. The reality is that is the truth for us all but we choose not to live into it.

A township is an informal settlement and a type of racially divided suburb within South Africa’s big cities, such as Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and Pretoria. I’ll be visiting Soweto township in Johannesburg later in the trip.

During apartheid and following the signing of the Group Areas Act of 1950, non-whites were forcibly removed from the center of Cape Town (everything around Table Mountain). They were moved to specific residential areas which had each been assigned to different ethnic groups.

However, Pass Laws forced men to leave their families at home and to go back to the cities to work. This led to men living in hostels in townships on the outskirts, and working in places such as factories, mines and other similar manual industries. They were homed in large dormitories with shared living facilities. I saw some of these hostels: concrete rows of rooms probably smaller than many of our bathrooms. When the Pass Laws were repealed, the wives and children were permitted to join the men, creating very cramped living conditions. This led to shacks popping up where suddenly the dormitories could no longer house the sheer number of people. As more and more people arrived, it quickly evolved into a township.

Langa is considered one of the safest of the Cape Town townships. As we walked the streets Ludumo seemed to know everyone. I was invited into homes and greeted by the residents. Langa is also one of the most manageable to visit in terms of size (just 1.5km square) whereas two of the other main townships, Gugulethu and Khayelitsha, are huge and take a lot longer to explore. The name ‘Langa’ derives from the name Langalibalele, a famous chief who was kept in prison on Robben Island for protesting against the government. There’s a street named after him within the township.

Around 70,000 people live peacefully in the township, most of whom belong to the Xhosa tribe. It was really interesting to hear some of them speak their click language. I tried it and it’s really hard. There are other African nationalities living there too, such as Somalians, Zimbabweans, Nigerians and Congolese. There are different clans there as well who have their own cultures and dress codes but who also speak Xhosa.

Langa township was established in 1923, making it the oldest in Cape Town. As mentioned, originally it was just men living here in dormitory style hostels and with black policeman patrolling. The men came from all over the country, but would tend to go home during Christmas and Easter for several weeks at a time. This led to many babies being born in September.

From Langa, the men traveled into Cape Town by train for their manual labor jobs in the city. When the women and children arrived to Langa in the late 1950s, whilst it led to cramped conditions and poorer sanitation, it did lead to health clinics and schools being built, which also led to more jobs within the township.

I am really thankful I went because some of my preconceived notions were shattered and I left inspired and full of hope. I think that’s what happens when we engage with people and places of difference. That’s why I love to travel. I put flesh and bone on ideas and stories I’ve only considered from a distance.

My guide showed me that there are several socioeconomic classes even within a township – not everyone lives in a shack (which is sometimes the picture we have in our heads of townships like Langa and Soweto). In fact, there was a middle class, and an upper class – an area he joked was the Beverly Hills super rich area. But he wasn’t far wrong: the houses in the township here were far larger and people drove fancy cars. It was a microcosm of any city all within the township.

The lower classes still live in shacks and shared spaces. The rent for these is free, as well as water. The only thing they have to pay for is electricity.

The lower middle class live in small brick and mortar homes, but due to overpopulation in the township, many share the space with other families. Many of this class live in government-built homes, most of which were constructed en mass in 1994 following the end of apartheid. People queued up for these homes, and the wait was (and still can be) as long as 10 years for one of these houses. Those who live in these do pay the government some rent.

The middle class live in small homes, with fewer families sharing the spaces. Again, the residents of these types of hoard pay rent to the government. They, along with the other lower economic classes, typically have to prepay for electricity and water.

The upper class live in bigger houses and are employed in professional roles such as accounting or in medical jobs, but choose to stay in Langa to give back and support the community which supported them.

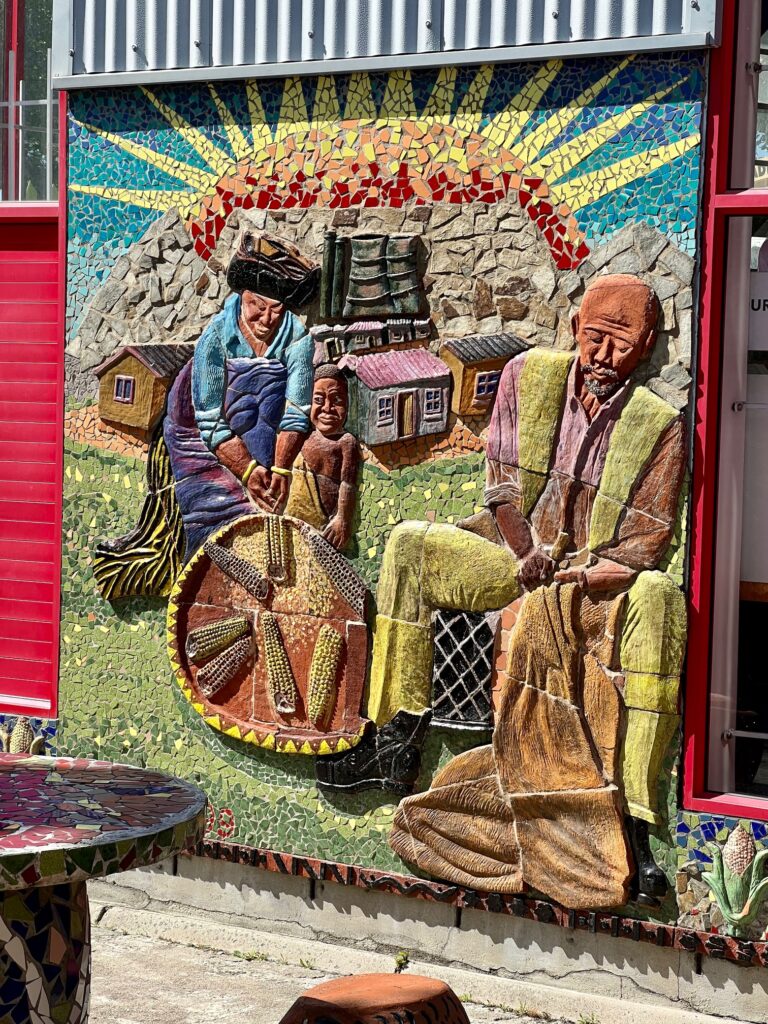

Ludumo also took me to a community center that was built to help youth learn crafting and art skills. The youth designed the beautiful mosaics that adorn the building and they have workshop spaces there. They are also able to sell what they make. I was able to purchase a necklace for Verity and meet the creator. I bought a beautiful sand painting of an African Wild Dog (which I hope to see on this trip) by a young man who is extremely talented. I saw beautiful mugs and other pottery, too, but space in my suitcase is getting tight. There is joy, and beauty, and entrepreneurship, and creativity are alive and well in Langa.

I think visiting a township, or any place that is off the normal tourist map, can be beneficial if done right. Let the residents speak for themselves and have a local show you around. It is an opportunity to learn and experience and broaden your understanding of the diverse ways in which people live, survive, and thrive.

The only path to true reconciliation is with and through one another. That means seeing, hearing, and engaging with those on the margins and those we may not normally commune without or even think about. It means visiting places like Langa and learning from them and investing in their future, because ultimately it’s an investment in all our futures.