Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Johannesburg and Soweto

October 8, 2022

Today, in Johannesburg I visited Soweto township and the Hector Pieterson Museum.

The museum is named for the young boy who was shot and killed by police on June 16, 1976, during the student marches protesting the mandatory use of the Afrikaans language in their schools to the exclusion of their native languages.

I was able to hear a first-hand account of the events of that day by Mama Antoinette, Hector’s older sister who was participating in the march.

On the morning of Wednesday, 16 June, 20,000 students in Soweto assembled in school grounds before beginning their march to Orlando Stadium where a protest against Afrikaans was to be held. On the way, not far from Phefeni Junior Secondary School on Vilikazi Street, 12-year-old Hector Pieterson joined the group which included his older sister Antoinette.

After a brief standoff with police, a shot was fired. Mama Antoinette recalled everyone running. And hiding. She showed us the place she hid and where she saw her brother standing out in the open. She called to him and he made his way to her, but there were more shots and confusion and they were separated. She said that spot is special to her because it was the last place she ever saw her brother alive. There were more shots and Antoinette saw a young man running up the street. She didn’t know what he was doing but then she saw the body he was carrying and recognized the shoes. She followed, crying, asking what he was doing with her brother. They finally arrived at a clinic where a doctor said Hector was dead.

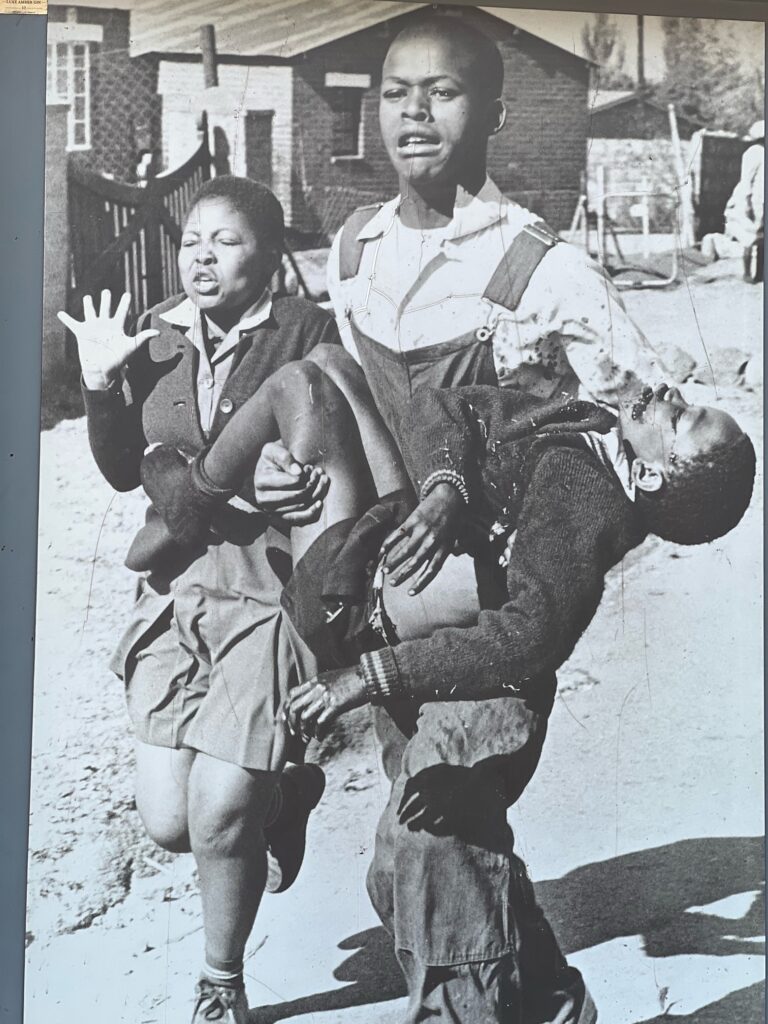

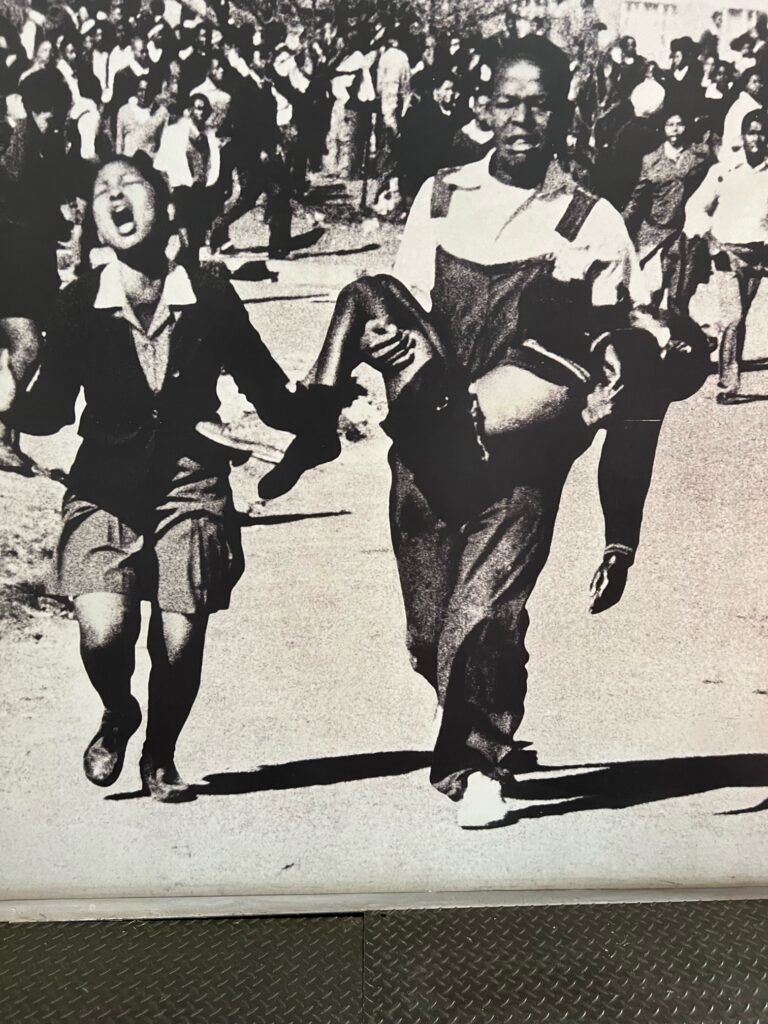

There are famous photographs of that day showing a dying Hector Pieterson, cradled in the arms of a fellow student, with his terrified sister running beside them. These images, taken by news photographer Sam Nzima, became a symbol of the resistance against apartheid. Today, June 16 is commemorated as Youth Day in South Africa.

I asked Mama Antoinette what reconciliation means to her. She said she felt 50/50 pain and hope. She echoed some of what Kgotso told me yesterday. She said only about 15% of white Africans seemed to have any interest in reconciliation but wanted black Africans to just move on and forget the past. She emphasized reconciliation takes two parties, and you can only do your own part.

She was able to take part in the Truth and Reconciliation in 1996 and share her story. At first, she didn’t want to, but realized she needed to in order to free herself of the burden and pain she’d been holding onto for so long. She shared her story and the commission asked if she wanted to know who killed her brother. She had to really think about that but eventually decided no, but she told the commission she forgave everyone. She said she needed to. It wasn’t just for them, but for her, too. She needed release from that moment as the definitive moment of her life. She needed to cut the chains that tied her to that tragedy and the men who shot her brother so she could be truly free. She had to forgive to find peace and finally live a new life. She told me, “we must let the dead rest in peace, but the living must live in peace rather than in pieces.”

She was in pieces until she was able to share her story with the commission and forgive others. There was no other way to wholeness and newness. While reconciliation takes two, forgiveness only takes one. She echoes Tutu’s famous phrase, “There is no future without forgiveness” because she has lived it.

After the museum we walked with Mama Antoinette through Soweto to the house where former South African President Nelson Mandela lived, on and off, for more than 14 years. The house has now become a museum that tells the tale, in sound, film, interpretive panels and guided tours, of the Mandela family during the apartheid era and beyond.

In his landmark autobiography, The Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela describes coming back to his house in Soweto in 1990 upon his release after 27 years in prison: ‘That night I returned with Winnie [his then-wife] to No. 8115 in Orlando West. It was only then that I knew in my heart I had left prison. For me No. 8115 was the centre point of my world, the place marked with an X in my mental geography.’

Vilakazi Street, where the Mandelas lived, is the only street in the world to have housed 2 Nobel laureates − the other being Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

In 1961, Nelson Mandela left No. 8115 for life on the run as a political activist. He was arrested and imprisoned in 1962. I wrote about that after my visit to one of his prisons, Robben Island.

His second wife, Winnie, who he married in 1958, was subjected to harassment, torture and imprisonment while living there on her own with the children.

I can only imagine the terror and struggle and anger that would often fill the house as her daughters had to watch their mother be dragged away by Apartheid police again and agin. This was routinely undertaken from 1962 until 1986, when Winnie returned from exile in Brandfort to continue life with her children. On 28 July 1988, Winnie and Nelson’s house was burnt to the ground by a fire after a conflict between the Mandela United Football Club which Winnie led, and pupils from Daliwonga High School. The community came together to help rebuild the Mandela’s house.

11 years later, on 16 March 1999, the house was awarded the status of a public heritage site, with Nelson Mandela as the Founder Trustee.

I learned a lot about the Mandelas’ lives and struggles at the house. His life was full of difficult circumstances and near impossible choices. What I’ve discovered through these different journeys and experiences is that I can’t judge people for what they do in contexts and situations so vastly different than my own. I can’t judge what an oppressed Irish Republican decides to do as they see they community destroyed by paramilitary groups any more than I can judge Mandela for some of the choices he made in his struggle for freedom for his people, or what people did in our own country from freedom from Britain or their supposed masters. We never know how we’d respond in similar circumstances unless we find ourselves in them. I pray we never do.

So we cannot and should not judge, but be willing to learn from them and their mistakes and successes and failures along the long roads to freedom.

There’s a lot of information out there about Mandela in the form of movies and biographies so I don’t want to rehash a lot of what you can easily find on your own, but here a few highlights that stuck out to me;

Mandela was expelled for joining a student protest while studying at Fort Hare. After a short stint as a security guard at a mine, he spent some time as a legal clerk in the law firm Witkin, Edelman and Sidelsky. His passion and natural aptitude for law was seen through his studies both in and out of prison, and the establishment of South Africa’s first Black law firm, Mandela and Tambo, with Oliver Tambo in August 1952.

His involvement in politics became more pronounced from 1944 when he helped to start the ANC (African National Congress) Youth League. The following years saw harsh punishment from the state against Mandela and his fellow political activists.

Some of the most notable movements in his activist career were leading the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto weSizwe, facing sabotage charges at the Rivonia Trial, and being sentenced to prison and banned from political activity multiple times. These moments led to a life imprisonment sentence in 1964. He was freed from prison in 1990 amid growing domestic and international pressure and fears of racial civil war by President F. W. de Klerk. Mandela was then elected President in 1994.

While there are a lot of opportunities to learn about Nelson, there aren’t as many to learn about his wife Winnie. Winnie was just as intelligent and driven as Nelson, finishing the top of her class for her social work degree in 1955. She chose a medical social worker job opportunity in Johannesburg over a scholarship in the USA. Nelson and Winnie were both charismatic and had a passion for equality and justice for their country and the world.

It must have been extremely difficult for Winnie in those early years (but also while Nelson was in prison). She walked into a life characterized by intense underground campaigning, which frequently meant she and Nelson couldn’t be together. The police raids in the dead of night became a constant feature in the family’s life. The police would raid the home and ransack the place. A few months after finding out about her first pregnancy, Winnie and other women embarked on mass action to protest the Apartheid government’s Pass Laws. She was arrested along with 1000 other women. She was appalled by the inhumane prison conditions. This intensified her resolve to keep fighting for justice and in the subsequent years she was continually harassed and imprisoned.

In 2016, the South African government recognized Winnie for her contributions to the liberation struggle with the award of the Silver Order of Luthuli. After a long illness, she passed on at the age of 81 on April 2, 2018.

While the Mandelas were active in the struggle for justice, they were also leading voices for reconciliation. Reconciliation can’t happen without justice and mercy. Mandela knew there was a divide in his country, a legal divide between races that became economic and philosophical and educational. Life was not good for the oppressed majority and anger was building. He knew there would need to be peace and reconciliation with the minority white Africa in power, but that couldn’t happen before justice was done. He worked for equality and for power-sharing and when that was accomplished he didn’t use his new power to hurt but to help hear the old wounds of his country.

We, too, need to reconcile over many things in our nation, but first we have to ask, has justice been done? Is there more work to do in order to make reconciliation possible? To ask for reconciliation without justice is to ask someone to say all the wrongs done to them are okay and can continue.

This doesn’t mean that justice has to be perfectly done. That’s never the case. No one will ever agree on when justice is complete or done the right way. But if there is no progress, it’s insulting and demeaning to expect reconciliation. It’d be like an abused woman being asked to reconcile with her husband while continuing to be abused and knowing it will continue to happen in the future. We would never suggest that (at least I hope not). The same is true for societies where there has been injustice.