News

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Adaptation

October 17, 2022

I am in awe at the beauty, resilience, and adaptability of God’s creation. This trip has wowed me with rocky coasts and cliffs, towering mountains, unique plants, colorful birds, and a myriad of fascinating creatures. Trips like this remind me of how much there is still to see, experience, and learn about creation. We can never exhaust the subject of God’s world because there’s always something new to see.

One of the interesting things I learned, while on a bush walk through the lowveld with a guide, is a unique back and forth struggle between an animal and its favorite food.

The sight of a giraffe browsing on the leaves of a majestic acacia tree is synonymous with Africa. It’s one of those things that was always in my mind when I imagined traveling to Africa. Giraffes love that tree more than any other and this fondness results in a fascinating ‘to and fro’ relationship between fauna and flora.

Giraffes can eat as much as 29 kilograms of acacia leaves and twigs daily. Herds of three or more giraffes spend hours browsing in acacia thickets, eating as much of the delicious leaves as they can. They don’t have it all their own way, however, because the acacia was not content to just be eaten!

Over time, the acacia tree has developed several clever defence mechanisms to prevent giraffes from munching on them unabated. As I’m sure most travelers to Africa can attest to (after painfully having it brush up against your arm on narrow roads when riding in open top vehicles), the acacia does not mess about when it comes to thorns. Taking their name from the Greek word for thorns – akis – some species grow thorns that are as long as 8-10 cm, and sharp as a knife. This make the tree much less enticing for animals to try and get to its leaves.

The wily giraffes have developed a counter to this though, by way of their incredible tongues. The giraffe’s tongue is about 45cm in length and highly prehensile. This allows the animal to successfully negotiate the bigger thorns and pull the leaves from the branch. Coupled with tough lips and palate that are basically numb to pain, the giraffe has seemingly overcome this particular hurdle set by the trees. But the acacia trees continued to adapt and change as the situation demanded.

Acacia trees have developed a further defense – the release of tannins. Tannins are water soluble, carbon based compounds found in plants that are very important to humans. Their chemical and physical properties allow the binding of alkaloids, gelatine and other proteins in the making of leather, or tanning. They are also used in food processing, fruit ripening and the making of wine and cocoa. But they’re no good to giraffes!

In the right amount, tannins can taste good — like in wine or tea — but sometimes when you drink a particularly strong red wine your mouth can feel a bit dry and bitter. That’s the tannins. When on our bush walk our guide had us chew on a particular leaf, then laughed at us because after a few munches we all had cotton-mouth. It was not a pleasant experience.

Besides tasting awful, tannins inhibit digestion by interfering with protein and digestive enzymes and binding to consumed plant proteins, making them more difficult to digest. When a tree starts feeling threatened and notices it’s getting damage from a giraffe, it releases more tannin into the leaves so the giraffes will stop eating it. What’s even more amazing is that acacia trees release a pheromone that is spread downwind to others trees, signaling them to release their tannin to protect themselves. The simultaneous tannin release by all nearby acacias essentially thwarts the greedy giraffe(s), who must now travel upwind to trees that have not yet been warned. This is why older and wiser giraffes have now learned to always eat upwind of other giraffes.

This back-and-forth battle between the giraffes and acacia trees reminds me of the need to change and adapt. The world around us is always changing. Sometimes that change can feel like a new opportunity and other times it can feel like an obstacle to overcome.

I believe a lot of the conflicts we have as a society come down to our inability or unwillingness to adapt. Sometimes we get frustrated over small things, like the need to adapt to new technologies when we finally got comfortable with the old ones. We resent when we have to adapt to new norms in culture, whether it’s the music or the fashion. I think every generation has complained about the music the next generation prefers.

In South Africa it’s been hard to adapt to the new black majority democracy. They are still trying to find their way. In the US we have to adapt to changing demographics, more diversity of religions, and new priorities. The choice is often to either adapt, fight for things to stay the same, or remain bitter, resentful, and withdraw as much as we can.

I’ve seen all three in the church. Church is not immune to change or the changes in society. The church certainly had to adapt to Covid. We have to adapt to new needs and challenges people are faced with, new constraints on time, and more. And when the church adapts and changes, people react in those same three ways. Some choose to fight the changes and try to keep the church exactly as they like it: same music, same activities, same look, same everything as if the church can be frozen in time as the world marches on. Others choose to be bitter and resentful about the changes and they withdraw more and more from the church until they are completely separated from the community. Others find a way to adapt to the changes in ways that best suit them and their needs. Everyone’s experience of church is different and that’s natural and okay. Some continue to livestream for various reasons, some attend Tuesday nights, some want to do as many things as possible while others find Sunday mornings more than enough.

Our church is as diverse as the natural world, so everyone’s experience of church is different. Just like the natural world, if we adapt, we can all inhabit this world and church together. It’s not always easy or quick, but we can find the right balance and live together in peace and harmony.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Victoria Falls

October 15, 2022

Today I went to Victoria Falls, but it’s known locally by other names in the languages of the various tribes such as Mosi-oa-Tunya meaning “the smoke that thunders.” Chongwe/Seongo is another historical tribal name meaning “the place of the rainbow.”

It is clear from archaeological sites around the Victoria Falls that the area has been occupied from around three million years ago. Stone artifacts from that time have been found as well as items from the Middle and Late Stone Age.

Stone Age inhabitants were eventually displaced by the Khoisan, who were hunter-gatherers that used iron implements. Later, Bantu people moved into the area and the Batoka tribes became dominant. Over time other tribes arrived including the Matabele and the Makololo. Descendants of these tribes are still living in the area today.

Members of the Makololo tribe were the ones who actually took the intrepid explorer David Livingstone, in dugout canoes, to see the falls. Livingstone, a Scottish missionary, was on a journey to find a route to the East Coast of Africa. Between 1852 and 1856 he explored the Upper Zambezi through to the river mouth. The falls were well known to local tribes and it was Chief Sekeletu who escorted Livingstone on November 17, 1855 to the viewing site.

Livingstone, on seeing the massive waterfall, named it after the British Monarch at the time, Queen Victoria. Later he recorded in his journal these famous words:

‘No one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.

David Livingstone

David Livingstone is known as the first European to see Victoria Falls. He returned again in 1860 for a more comprehensive study and was accompanied by John Kirk, a fellow explorer. Other European visitors that followed included a Portuguese explorer, and Emil Holub, a Czech explorer who made the first detailed plan of the area. Also British artist Thomas Baines, who painted some of the earliest pictures of the falls.

But was Livingstone the first European to see the falls? Probably not. Portuguese explorers came through on their way to Mozambique quite often, they just never recorded what they saw or told anyone. For right or wrong, credit often isn’t given unless you become a witness and share what you’ve seen, heard, or experienced. The local indigenous people knew of the falls, but that knowledge never spread beyond their local borders. The local tribes still give Livingstone a lot of credit because he helped make their falls famous.

That gets me thinking about the importance of sharing our own experiences. I hear so many Christians say that they don’t talk about their faith because it’s a personal thing. Well, that’s the exact opposite of what the Bible says. Christianity was never meant to be done alone. It’s not personal; it’s communal.

We are supposed to share the good news. We are supposed to report what we’ve seen, heard, and experienced of God or it doesn’t really matter. The good news of the Gospel is too big and too wonderful not to share. That’s what Livingstone thought about the falls. He had to report back and share what he’d seen. It was too good to keep to himself. That’s how we should feel about the Gospel, about our faith, and church. It doesn’t mean we are pushy or forceful, but we need to share. We need to talk about experiences of forgiveness and reconciliation. The world needs to know. Because once we know the good news, once we know peace and reconciliation is possible, then we are more likely to go and search for it ourselves and find ourselves at that place of peace.

Once word got out about the falls, Anglo traders started to arrive in increasing numbers and a rustic settlement was built on the riverbank (now Zambia) called Old Drift, the crossing place for the Zambezi River prior to 1905.

Visitors from what was the Transvaal region of South Africa began to make their way by ox wagon, on horseback or on foot, to see Victoria Falls. However, malaria was a serious problem in Old Drift causing the settlement to be relocated to its present site, now the town of Livingstone, Zambia.

Victoria Falls really came into its own when Cecil John Rhodes, a politician and entrepreneur ,commissioned the building of the now-famous landmark Victoria Falls Bridge, to cross the Zambezi River. The Victoria Falls bridge was completed in 1905 and became a major transport route for road and rail traffic, trade and enterprise in Africa. That bridge is still standing today and is used daily by cars, trucks, and pedestrians crossing from Zimbabwe to Zambia. I also made the trek over the historic bridge.

The falls are magnificent, and we went during the low water period. When it’s high water you can barely see anything through the mist. God’s world is truly amazing. There’s so much to see and learn and experience. There’s so much worth sharing and reporting and so others want to experience the majesty of creation. I’ll talk about that more tomorrow.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Travel Groups

October 14, 2022

I’m always a little worried when I do a group travel experience. What the group will be like? Will we get along? Will someone really annoy me? Will I really annoy everyone else? Will the group actually spoil the experience? I have these fears, but each time I’ve travelled with groups of strangers I come away from the experience with new friends. Every group I’ve been with has worked well together and actually added to my trip, not taken away from it.

I’ve been thinking about why that’s the case. Perhaps I have just been lucky. I’ve heard horror stories of bad groups and people on trips who just don’t get along very well. There is often perhaps one person you may clash with, but there are enough other people to balance that out. My mother has been on more trips than me, and has had similar experiences with her groups. She still connects with people from trips she went on long ago.

On this trip we had young couples, an adult family of four, and single people. We had ages ranging from late twenties to early 70s. We had people from the US, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and England. We all had diverse jobs and travel experiences, but we really came together as a group and enjoyed each other. Having such a diverse group made the trip more enjoyable. It was fun to experience these once-in-a-lifetime things with strangers who have become friends.

Perhaps travel brings out the best in people. We all want a great trip and are full of excitement. But then again, travel can also be stressful. Maybe it’s because we are in a low stakes environment. We aren’t competing for limited resources and our interactions won’t have long-term consequences. Maybe it’s because we feel free to disengage from the contentious political issues of the day; We aren’t paying attention to the latest election news and don’t feel the need to discuss it. Maybe we all feel less stressed, so we are our best selves when together. There are many possible reasons and factors, but it reminds me that we can live better together. It is possible.

In all likelihood I will never see any of these people again, but they will forever be part of one of the best experiences of my life. I’m glad each of them were a part of it. For a short while we were a community that cared for one another, helped one another, and celebrated with each other. It reminds me that we have more in common than we sometimes think. We have so many common goals and dreams and we often let a few issues, though important, divide us and keep us from community together.

Maybe I’ve just been lucky, but I choose to believe that if we put some of the stress, competition, and contentious issues behind us then we could be a good and beautiful community with almost anyone. I know we can’t live in a world where there is no stress, competition, or contentious issues, but perhaps when we believe and learn it is possible for us to be a loving community together we can do it despite and even with those challenges. Traveling with groups gives me that hope and experience. It’s not easy to replicate at home, but maybe that’s because we don’t try as hard as we could. We stay in our bubbles and assume the worst about each other. Maybe we just need a chance to be forced out of our bubbles with others for a while and experience the good and beautiful community diversity offers and affords.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Ubuntu

October 13, 2022I spoke two weeks ago in worship about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that Archbishop Desmond Tutu led in South Africa. The Commission allowed people to share their story and hear the stories of others, often the ones who did them and their loved ones harm.

Tutu shares about the story about Mrs. Mhlawuli whose husband was killed. She spoke about the disappearance and murder of her husband, Sicelo. She recounted all the ways his the autopsy showed he had been tortured, from apendages being cut off to having acid poured on his face. Then it was his daughter’s turn to speak. She was eight when her father died. Her brother was only three. She described the grief, police harassment, and hardship in the years since her father’s death. And then she said, “I would love to know who killed my father. So would my brother.” Her next words stunned Tutu and left him breathless. “We want to forgive them. We want to forgive, but we don’t know who to forgive.”

I’m often shocked and outraged by what humans can do to one another. We’ve seen it recently with the war in Ukraine and the reports of the bodies found in graves that have signs of torture and mutilation. But, I am often in awe at humans’ capacity to heal and mend and love. This family wanted to forgive after so much loss and pain. They wanted a new future, a better way of living together with one another and God. I think we all want that, at least I hope we do.

I believe we want this because our inherent nature is to be in good and beautiful communion and community with another. When we witness the anguish and harm we have caused, when we ask others to forgive us and make restitution, when we forgive and restore our relationships, we return to our inherent nature.

Our nature is goodness. God made us good. Yes, we do much that is bad, but our essential nature is good. If it were not, then we would not be shocked and dismayed when we harm one another. When someone does something ghastly, it makes the news because it is the exception to the rule. We live surrounded by so much love, kindness, and trust that we forget it is remarkable. Forgiveness is the way we return what has been taken from us and restore the love and kindness and trust that has been lost. With each act of forgiveness, whether small or great, we move toward wholeness. Forgiveness is nothing less than how we bring peace to ourselves and our world.

I have been shocked, amazed, and overwhelmed by the stories I have heard here. In South Africa, the society came together to intentionally choose to seek forgiveness rather than revenge. It was not unanimous and perfect, there are still problems in South Africa, but that choice averted a bloodbath. For every injustice, there is a choice. Every day, we can choose forgiveness or revenge, but revenge is always costly. We see it in politics and personal life. Choosing forgiveness rather than retaliation ultimately serves to make you a stronger and freer person. Peace always comes to those who choose to forgive. I met so many gracious and kind people of all races and backgrounds here in the rainbow nation, so I see how they were able to come together. Of course there are still disagreements and problems, but the people here are wonderful. I am confident they will continue to find the right way forward together.

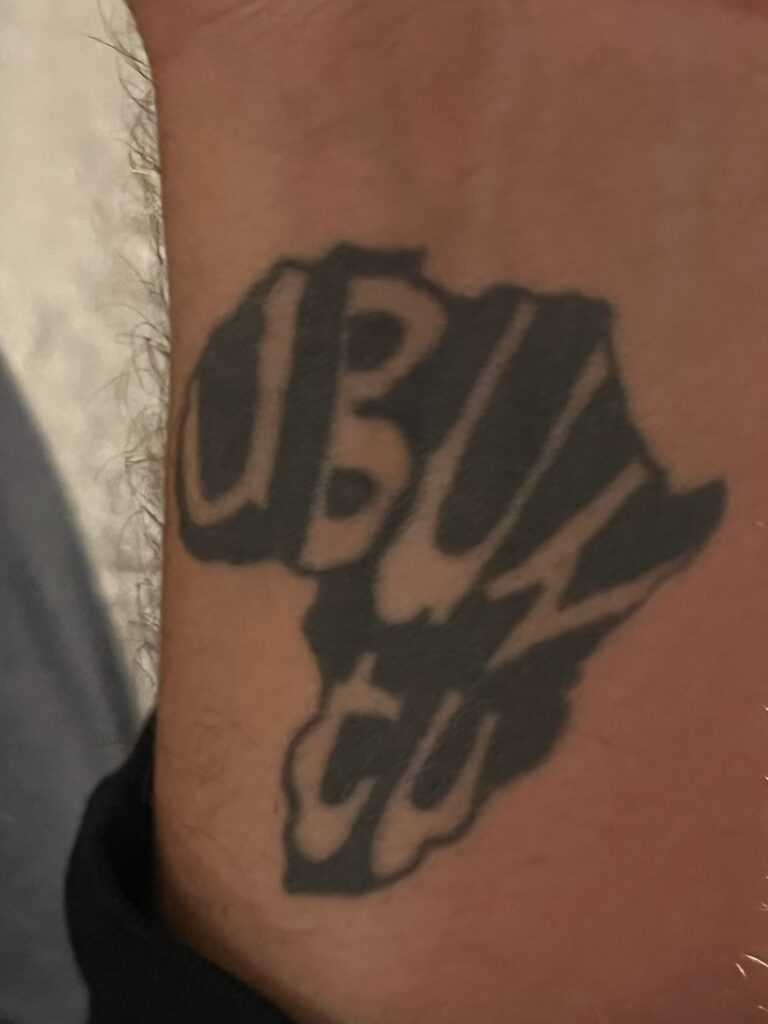

In South Africa, I learned that Ubuntu is their way of making sense of the world. The word literally means “humanity.” Our guide had this tattooed on his arm inside a picture of the African continent. It is the philosophy and belief that a person is only a person through other people. In other words, we are human only in relation to other humans. Our humanity is bound up in one another, and any tear in the fabric of connection between us must be repaired for us all to be made whole. This interconnectedness is the very root of who we are.

This is why reconciliation is so important. We belong together and to one another. We are bound to one another, and we must find ways to choose to forgive and reconcile so all those tears in the fabric of connection can begin to be mended.

We can start small. Reach out to those who we need to reconcile with and forgive. Listen to the pain and admit when we have caused it. Choose mercy instead of revenge. Choose connection not separation. Choose love.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Hunting

October 13, 2022

I don’t know about you, but I often find myself making judgments about people and situations without much information and experience.

One example of this is how I’ve felt about people who hunt African animals. Perhaps you’ve seen the pictures on social media of someone next to some large African mammal like a lion or elephant. Stamped on the picture is the person’s name and the instructions to spread their shame. I admit having negative feelings toward those people. How could they? Why would you want to kill such a beautiful animal? Why would you take away the opportunity for others to see it?

The problem was that I didn’t know those people or their motivation. I didn’t know the situation of the hunt or the rules. And yet, I made negative judgments about them. We do this all the time. With the bare minimum of information, we judge one another and, in the process, judge ourselves superior: morally, ethically, politically, or religiously.

So I decided to ask our guide about hunting in South Africa. First, we need to clarify the difference between hunting and poaching. Poaching is the illegal killing of an animal, whether it’s for a small piece of the animal (like the horn of a rhino) or for the meat to sell or feed a family (like a kudu or springbock). Hunting is a legal activity.

In South Africa, hunting is only allowed on game reserves and it’s strictly regulated. Just like in Pennsylvania, wildlife experts determine the carrying capacity of habitats and use hunters to bring down numbers when necessary. These hunters then are able to use the meat to feed their families. Trophy hunting (for lions, elephants, etc) is similar. On some occasions there are too many males of a particular species in an area and instead of having them kill each other, a hunting permit is given. The hunter can only take that specific animal in a specific time period. Or sometimes an animal is older and the wildlife management team knows it will soon be killed by others or die naturally. Again, the hunter has to find that specific animal or they are out of luck.

The money from the permits is then used by the reserves for conservation and continued protection of all the animals.

It is perfectly justifiable to be against all kinds of hunting, or just trophy hunting. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, just as some people choose to be vegans and others love to eat meat. But, either way, it’s important to have the right information before judging, and especially, criticizing others.

We often just don’t take the time to listen to those we judge, seek the right information, or ask the right questions. I hope our Engage Stories programs are a way to listen to others and practice asking the right questions of each other so we can learn and have more informed opinions.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

2023 Stewardship Campaign

October 12, 2022

In the past week, you should have received a stewardship mailing including a letter, magnet, and pledge card. Stewardship Sunday is Nov 13, the day our pledges will be dedicated for 2023. That afternoon we’ll celebrate with the “Basically Broadway” talent show.

Your financial support is essential for furthering the mission and ministry of Derry Church. Please take a moment to pledge online, mail your estimate of giving card to the church, or bring it with you on or before Nov 13 and place it in one of the offering boxes. Estimate of giving cards are also available at church.

Questions? Did we miss sending you a mailing or a magnet? Contact Sandy Miceli.

If you have been using our online giving platform and you are making a change to your pledge for 2023, you will need to apply that adjustment in your Vanco account. Thank you for your ongoing support of Derry Church.

Second Friday Meals on Wheels Volunteer Needed

October 12, 2022Derry Church teams deliver meals to homebound residents in Derry Township every Friday. The team that delivers meals on the second Friday of each month is looking for a new driver to join them.

Deliveries begin at 8:30 am at the Church of the Redeemer United Church of Christ on Chocolate Ave in Hershey, and takes about an hour. Substitutes are available when you need a month off. Click here to read more about how Derry Church participates in the program. For more information and to volunteer, contact Mary Day.

Rock & Roll Halloween Dance Benefits Downtown Daily Bread

October 12, 20224 PM SUNDAY, OCT 30 AT THE ENGLEWOOD, 1219 WEST END AVE, HERSHEY

In the Harrisburg community, Downtown Daily Bread is the only walk-in shelter, soup kitchen, and services for all hungry and homeless individuals. Come on out and support one of Derry’s mission partners: enjoy a fun evening featuring music by Tom Slick and the Converted Thunderbolt Greaseslappers. Costumes encouraged! Admission $30: purchase online or at the door.

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: District Six

October 11, 2022

I had the opportunity to visit the District Six Museum in Cape Town and tour it with a former resident. The museum is located in an old Methodist church that survived the destruction of the area. It’s odd because all around you can see the modern skyline of Capetown and nice cafes, but the scars of apartheid still exist in dilapidated buildings and lifeless vacant spaces in the midst of an otherwise bustling city. District Six was one a thriving melting pot, a community where everyone knew their neighbors. Generations had lived there together.

The vacant lots are the remnants of the forced removals which took place in District Six in the 1970s.

The area known as District Six got its name from having been the Sixth Municipal District of Cape Town in 1867. Its earlier unofficial name was Kanaldorp, a name supposedly derived from the the series of canals running across the city, some of which had to be crossed in order to reach the District (kanaal is the Afrikaans for ‘canal’.) Over time, some people called District Six Kanaladorp, (kanala being derived from the Indonesian word for ‘please’), and its likely that the name stems from a fusion of the two meanings.

So what happened in District 6? We have to go way back to understand the not-so-far-back.

Since the 17th century, European colonists coveted South Africa. The Cape of Good Hope, the Southwestern tip of Africa, was once the starting point for ambitious sailors with dreams of arriving in the mysterious East. South Africa was successively colonized by the Dutch in the 17th century and by the British in the 19th century. The discovery of diamonds in the 1860s in Kimberley and the discovery of gold in the 1880s in Witwatersrand and Johannesburg only made the country more attractive to colonists.

People from around the world found a home in the area. District Six, one of the main municipal districts in the center of Cape Town, housed diverse people from Dutch colonies in India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Many Muslims also dwelled in Cape Town, and traveled from Indonesia, the country with the largest Muslim population in the world.

The wealth of religious diversity developed into inclusiveness rather than hostility, said former resident Noor Ebrahim. Ebrahim grew up in District Six and went to a mosque in northern District Six with area families as a child. Today, he works in the District Six Museum and still goes to the mosque from his childhood every day.

“We loved each other in District Six,” Ebrahim said. “When my Christmas comes, they call it Eid. All my friends, Jewish, African, Christian, Hindu, you name it, they would put on a fez, and they would go with me to my mosque. I think that made District Six such a great place.”

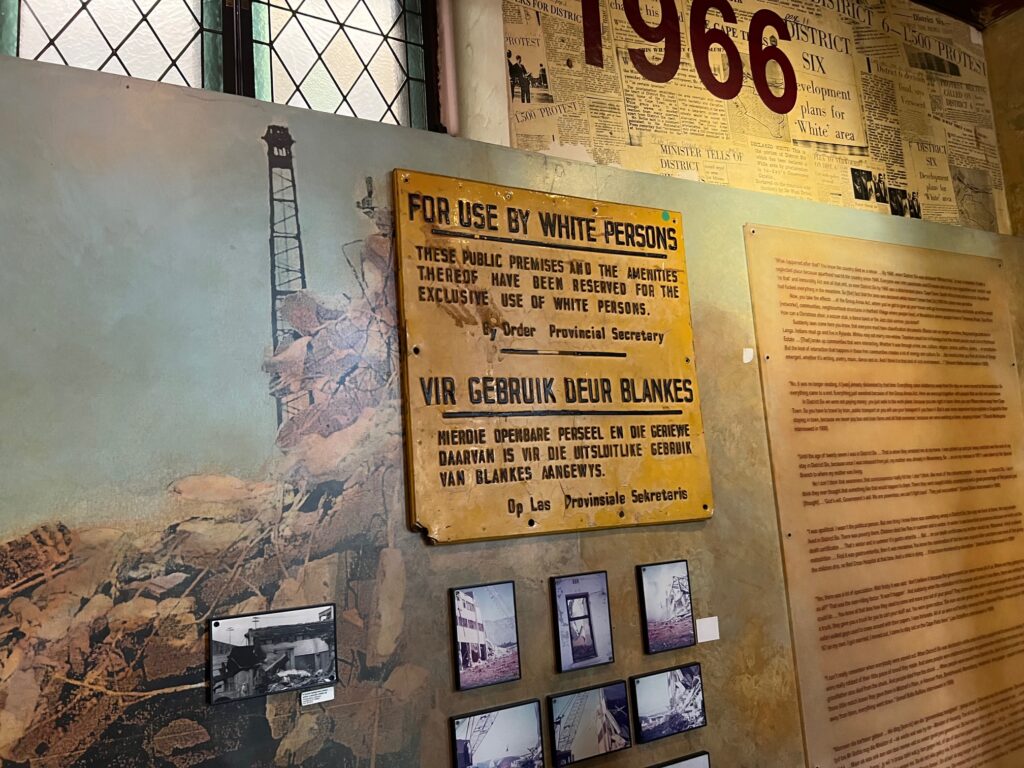

The 1950s marked the era of apartheid in South Africa. The government began to racially classify all residents in the country. South Africans were declared white, black, Asian or colored. Most residents of District Six came to be classified as so-called colored or mixed blood. Legislation (including the Population Registration Act, Bantu Education Act, Group Areas Act and Immorality/Mixed Marriages Act) was designed to segregate Europeans from non-Europeans.

“Within that apartheid framework, they thought society would be contaminated by the colored people,” said Joe Schaffers, former resident of District Six and education officer at the District Six Museum.

Classification was arbitrarily based on appearance and judged by government officials. Herman, for instance, spoke Afrikaans and was not initially classified under the system. In 1951, when he was eight years old, he went to have what was called “the pencil test.”

Officials used the test as a way to determine a person’s racial grouping. If a pencil could be run through a person’s hair with ease, a person would be declared white. If the pencil became stuck in a person’s hair, they would be called colored or African. Herman and his parents were categorized as “Cape Colors” as a result of the test.

Although many of Herman’s family members were labeled as colored, his uncle married a white woman and was classified as white. “Many of us rejected that,” Herman said. “They denied their own roots and took on the identity of oppressor, which was the white people. In my family on both sides, there were divisions and people who never really met.”

The subjective nature of the racial groups allowed some people to manipulate the system. Many people took the pencil test in an attempt to be labeled as white since the apartheid system afforded special privilege to this group. White South Africans were given better jobs, education and housing. Some of the White South Africans admitted to looking to the US as a template for their racial discrimination.

The apartheid government took further steps to divide the population following this period of population classification. On Feb. 11, 1966, the government declared District Six to be a white-only residential area under the Group Areas Act. Around 60,000 non-white residents of District Six were forced to move to townships outside of the city center. Residents were moved into the townships according to their racial classification. These townships were located in the dry and dusty Cape Flats area outside the city and often had poor infrastructure.

As a result of these acts, residents could only go to schools, churches and other public spaces reserved for their racial groups. Skin color and bloodlines determined the boundaries of a person’s life. If a white man wanted to visit his wife who had been classified as “colored,” he had to apply for a permit to even enter a colored township, said Schaffers.

Most of District Six’s residents were classified as colored under apartheid. As a result, most residents were affected by the forced removal. Apartments, churches and shops were leveled to the ground in the years after the Group Areas Act. New buildings such as the Cape Peninsula University of Technology were built upon the destroyed buildings, including Ebrahim’s home.

“If you owned property in these areas, they’d ask you to move and offer you a place of lower value,” Schaffers said. “If you refused, they would take this property and offer you an even worse offer than the first one.”

Once people were relocated to the Cape Flats, the government failed to sufficiently support the area’s explosive population. Basic necessities like electricity could be scarce, and the townships breed poverty and gangsters.

“It’s not meeting the needs of people living there,” said Chrischené Julius, manager of Collections in District Six Museum. “It becomes a space that really becomes a symbol as what the Group Areas Act actually achieved.”

Society has gradually improved since apartheid ended in 1994. The current government has pledged to create access to good education and jobs for all people, but change is never swift or complete.

The District Six Museum was established in December 1994 to preserve the memory of District Six and to remember the lessons of segregation. The museum plays a role of education and shows people that the city center is a public space for all people, not a specific race. They focus on people’s stories and memories so the museum is more like a memory box than traditional history museum. Sometimes memory contradicts records, but they allow the memory to remain intact as it is remembered by different residents even if those memories contradict each other. The museum keeps alive the stories and struggles of the residents who lives with the racism and corruption of apartheid.

“The apartheid racism is not something that only white people show towards black people” Julius said. “It’s part of our culture.”

Although the government has issued the Land Restitution Act as a measure to allow former residents to move back into the area, execution is still lagging. Only 200 residents have been able to live back of the 60,000 removed. Many former residents have died, complicating how ownership of the land should be determined. Living expenses in the area in the area are also high, and many who have lived in the Cape Flat area for decades cannot afford to move back to their former lands. The act also fails to address where current residents should relocate and how land covered by new buildings can be allocated to former residents. There are still 1,260 validated claims to land in the area.

Many of the residents feel like they cannot reconcile yet with the government that took them from their homes and neighbors because restitution has not been made. They say it’s an unfair to talk to them about reconciling when the wrongs have not yet been made right. The pain and loss is still very real, so they feel there can it be peace and mercy without any justice. Imagine having so much taken from you, then being asked to just forget it and live in your new, more difficult reality, but also being expected to forgive and let the loss go for the sake of peace. It’s an unfair ask and not one someone who has ever experienced something similar would ever ask. Those kinds of desires and demands on others come from a place of privilege that prioritizes its own peace and well-being over justice.

Learning about District 6 did not feel very foreign to me, as horrible as what happened here was. I grew up learning about forced removal of the Cherokee Nation in my native South Carolina, and many other forced removals of native peoples across the US, so their land could be redeveloped. I’ve learned about redlining and ghettos and the Jim Crow south. We have our own culture of racism, and when we say we are in a post-racist society, we aren’t being honest with our past or our present. We haven’t righted many of the wrongs our society is guilty of, even if we ourselves had no direct role in it. I think we can acknowledge the ways we have improved and progressed, but as in District 6 there is still work to be done. Peace and mercy are important but we need to learn and acknowledge the truth and work for justice if we really believe in reconciliation.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

SaBbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Safari

October 10, 2022

I had the opportunity to go on a safari drive in Kruger National Park which has always been a dream of mine. I remember watching the nature shows as a child of lions in Africa hunting zebra and springbok. I love all those David Attenborough narrated shows about the wilds of Africa.

I always liked the big cats and enjoyed watching them hunt. I found myself pulling for the lion or cheetah to win in its chase of the gazelle or battle with the wildebeest. I wonder why that is. Why did I side with the predator? Was I training myself early on to be the predator and not the prey? Did I subconsciously identify myself with the top of the social food chain? I’m not sure, but I pulled for the lions. I more closely identified with the narrative of the predator.

So I was hoping to see a big cat take down an animal on my safari drive. Now, I knew this was unlikely for several reasons. A big cat probably won’t hunt with us watching and we probably won’t be out on safari during prime hunting times, but I still hoped.

It’s interesting to see a big cat stalk and take down prey. The blood and gore wouldn’t bother me. The death wouldn’t either. I’ve been around death. I even hunt. But I discovered there is something that would bother me.

As I went on safari I saw animals living their lives. I saw family units of animals and followed them around. Sometimes you almost get a sense of knowing them if you watch them enough. If I came back the next day and saw that same family of zebras and suddenly saw a lion stalking the youngest, I wouldn’t want that lion to get a meal. It’d be hard not to shout out a warning.

Why? I admit wanting to see a lion kill a zebra, so why not this zebra. It’s because I know this zebra now. We’ve met. It’s not a faceless zebra or gazelle. I’ve experienced it.

I’ve found the same to be true when watching nature shows. When the narrative is told from a zebra or wildebeest’s perspective I don’t want it to lose a member of its family. When to documentary is told from the lion’s perspective I don’t want it to go hungry.

So much of our opinions and desires are based on the narratives we hear and the perspectives through which we encounter the world. Too often, we limit ourselves to very narrow narratives and perspectives: ones that are comfortable and familiar to us.

As part of my larger sabbatical process I participated in a six-month learning journey with reconciliation communities in the US and across the UK. As part of that, I learned more about counter narratives.

Counter-narrative refers to the narratives that arise from the vantage point of those who have been historically marginalized. The idea of “counter-“ itself implies a space of resistance against traditional domination. A counter-narrative goes beyond the notion that those in relative positions of power can just tell the stories of those in the margins. Instead, these must come from the margins, from the perspectives and voices of those individuals. A counter-narrative thus goes beyond the telling of stories that take place in the margins. The effect of a counter-narrative is to empower and give agency to those communities. By choosing their own words and telling their own stories, members of marginalized communities provide alternative points of view, helping to create complex narratives truly presenting their realities.

I’ve been more intentional about opening myself up to counter narratives by reading diverse authors and listening to communities different from my own. One of my goals with Engage Stories at Derry is to eventually bring in storytellers who can share counter narratives with us from their own experiences so we can create a space to hear them.

I want to be more intentional about hearing a variety of narratives about the world and the things happening around me. I want to make a space for the counter narratives. I want to really question if I’m only considering one dominant perspective when thinking about a situation, conflict, or problem.

I think this is extremely important for any reconciling community. If we aren’t making space for the counter narratives and we aren’t listening to diverse perspectives then we can’t really do the work of reconciliation.

I can still appreciate and love big cats. I can still want them to hunt and kill and eat. But at the same time I can appreciate the beauty and majesty of the zebra and antelope and hope they find ways to survive and thrive. I know both can’t always happen, and I know my experience may color how I feel in any specific situation. But I think it’s important to understand both animals and their perspectives and struggles as I consider the larger picture of life in the wild.

The same is true for life in Hershey. Life will not be perfect. Someone will get a job and someone won’t. Someone will win and someone will lose. But I hope I can do a better job listening and making space for the variety of perspectives and experiences that exist here so perhaps we can find better ways to live together and with God.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Cape Town #1: Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden

Posted in Uncategorized on by Susan George. Edit

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Langa Township

October 9, 2022

I visited Langa township in Cape Town with a local resident who showed me around, introduced me to people, and told me stories. I entered into small rooms that served as a home for a whole family, saw the businesses run out of small shipping containers, and the old courthouse pass office that regulated the movements of the residents.

I’ve heard about the townships in South Africa since high school when I read Cry, the Beloved Country, but I haven’t taken the time to really understand them or why such disparity exists in different parts of the same city. But it’s a reality in every city from Cape Town to Chicago.

I admit feeling a little odd touring a township. It feels a bit like poverty tourism, which is uncomfortable. I felt a little better being with a resident and learning from him, but there’s still a voyeuristic feeling to it. I wanted to learn and be more aware of Langa’s history and present. I wanted to see them and not just skip over these important areas of Cape Town in favor of the typical tourist locations. At times it was upsetting to see how some people had to live, and yet there was joy in the community. I saw little boys playing with cars they made out of milk cartons and caps. I saw women preparing sheep heads to sell for meat, and women braiding each other’s hair in small communal spaces. My guide, Ludumo, told me how everything was really communal there. People share cooking spaces, bath houses, lines for drying clothes and everything else. They work together and rely on each other because they need to. There’s no other way. The reality is that is the truth for us all but we choose not to live into it.

A township is an informal settlement and a type of racially divided suburb within South Africa’s big cities, such as Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and Pretoria. I’ll be visiting Soweto township in Johannesburg later in the trip.

During apartheid and following the signing of the Group Areas Act of 1950, non-whites were forcibly removed from the center of Cape Town (everything around Table Mountain). They were moved to specific residential areas which had each been assigned to different ethnic groups.

However, Pass Laws forced men to leave their families at home and to go back to the cities to work. This led to men living in hostels in townships on the outskirts, and working in places such as factories, mines and other similar manual industries. They were homed in large dormitories with shared living facilities. I saw some of these hostels: concrete rows of rooms probably smaller than many of our bathrooms. When the Pass Laws were repealed, the wives and children were permitted to join the men, creating very cramped living conditions. This led to shacks popping up where suddenly the dormitories could no longer house the sheer number of people. As more and more people arrived, it quickly evolved into a township.

Langa is considered one of the safest of the Cape Town townships. As we walked the streets Ludumo seemed to know everyone. I was invited into homes and greeted by the residents. Langa is also one of the most manageable to visit in terms of size (just 1.5km square) whereas two of the other main townships, Gugulethu and Khayelitsha, are huge and take a lot longer to explore. The name ‘Langa’ derives from the name Langalibalele, a famous chief who was kept in prison on Robben Island for protesting against the government. There’s a street named after him within the township.

Around 70,000 people live peacefully in the township, most of whom belong to the Xhosa tribe. It was really interesting to hear some of them speak their click language. I tried it and it’s really hard. There are other African nationalities living there too, such as Somalians, Zimbabweans, Nigerians and Congolese. There are different clans there as well who have their own cultures and dress codes but who also speak Xhosa.

Langa township was established in 1923, making it the oldest in Cape Town. As mentioned, originally it was just men living here in dormitory style hostels and with black policeman patrolling. The men came from all over the country, but would tend to go home during Christmas and Easter for several weeks at a time. This led to many babies being born in September.

From Langa, the men traveled into Cape Town by train for their manual labor jobs in the city. When the women and children arrived to Langa in the late 1950s, whilst it led to cramped conditions and poorer sanitation, it did lead to health clinics and schools being built, which also led to more jobs within the township.

I am really thankful I went because some of my preconceived notions were shattered and I left inspired and full of hope. I think that’s what happens when we engage with people and places of difference. That’s why I love to travel. I put flesh and bone on ideas and stories I’ve only considered from a distance.

My guide showed me that there are several socioeconomic classes even within a township – not everyone lives in a shack (which is sometimes the picture we have in our heads of townships like Langa and Soweto). In fact, there was a middle class, and an upper class – an area he joked was the Beverly Hills super rich area. But he wasn’t far wrong: the houses in the township here were far larger and people drove fancy cars. It was a microcosm of any city all within the township.

The lower classes still live in shacks and shared spaces. The rent for these is free, as well as water. The only thing they have to pay for is electricity.

The lower middle class live in small brick and mortar homes, but due to overpopulation in the township, many share the space with other families. Many of this class live in government-built homes, most of which were constructed en mass in 1994 following the end of apartheid. People queued up for these homes, and the wait was (and still can be) as long as 10 years for one of these houses. Those who live in these do pay the government some rent.

The middle class live in small homes, with fewer families sharing the spaces. Again, the residents of these types of hoard pay rent to the government. They, along with the other lower economic classes, typically have to prepay for electricity and water.

The upper class live in bigger houses and are employed in professional roles such as accounting or in medical jobs, but choose to stay in Langa to give back and support the community which supported them.

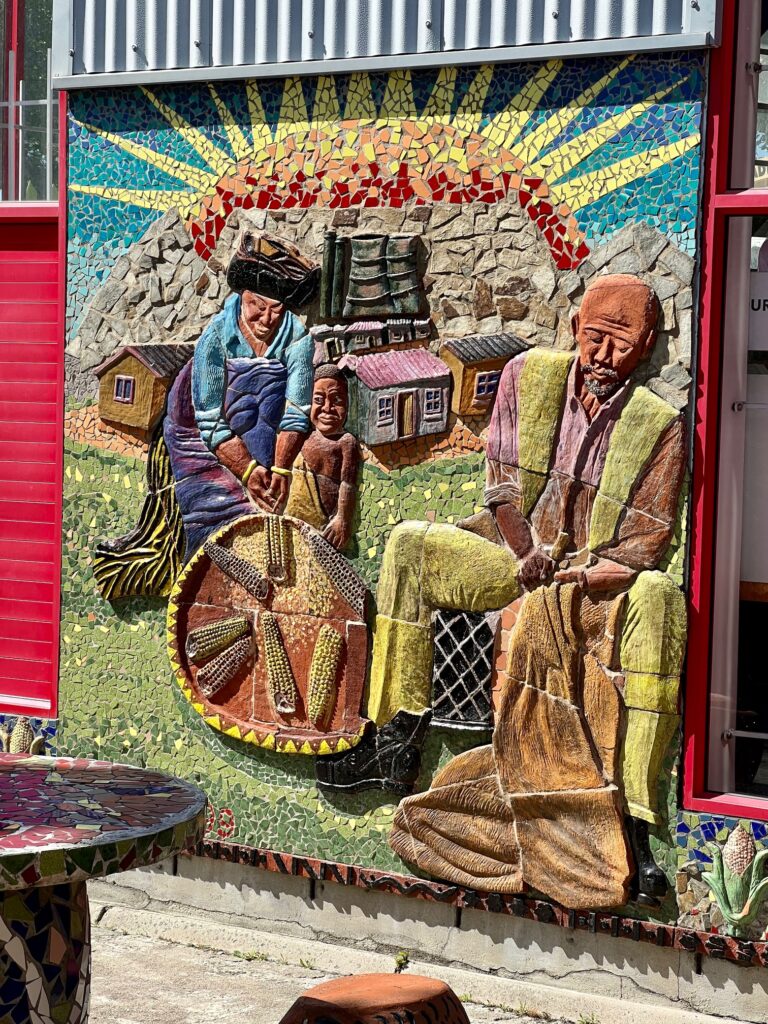

Ludumo also took me to a community center that was built to help youth learn crafting and art skills. The youth designed the beautiful mosaics that adorn the building and they have workshop spaces there. They are also able to sell what they make. I was able to purchase a necklace for Verity and meet the creator. I bought a beautiful sand painting of an African Wild Dog (which I hope to see on this trip) by a young man who is extremely talented. I saw beautiful mugs and other pottery, too, but space in my suitcase is getting tight. There is joy, and beauty, and entrepreneurship, and creativity are alive and well in Langa.

I think visiting a township, or any place that is off the normal tourist map, can be beneficial if done right. Let the residents speak for themselves and have a local show you around. It is an opportunity to learn and experience and broaden your understanding of the diverse ways in which people live, survive, and thrive.

The only path to true reconciliation is with and through one another. That means seeing, hearing, and engaging with those on the margins and those we may not normally commune without or even think about. It means visiting places like Langa and learning from them and investing in their future, because ultimately it’s an investment in all our futures.

READ MORE SABBATICAL NOTES:

Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: Johannesburg and Soweto

October 8, 2022

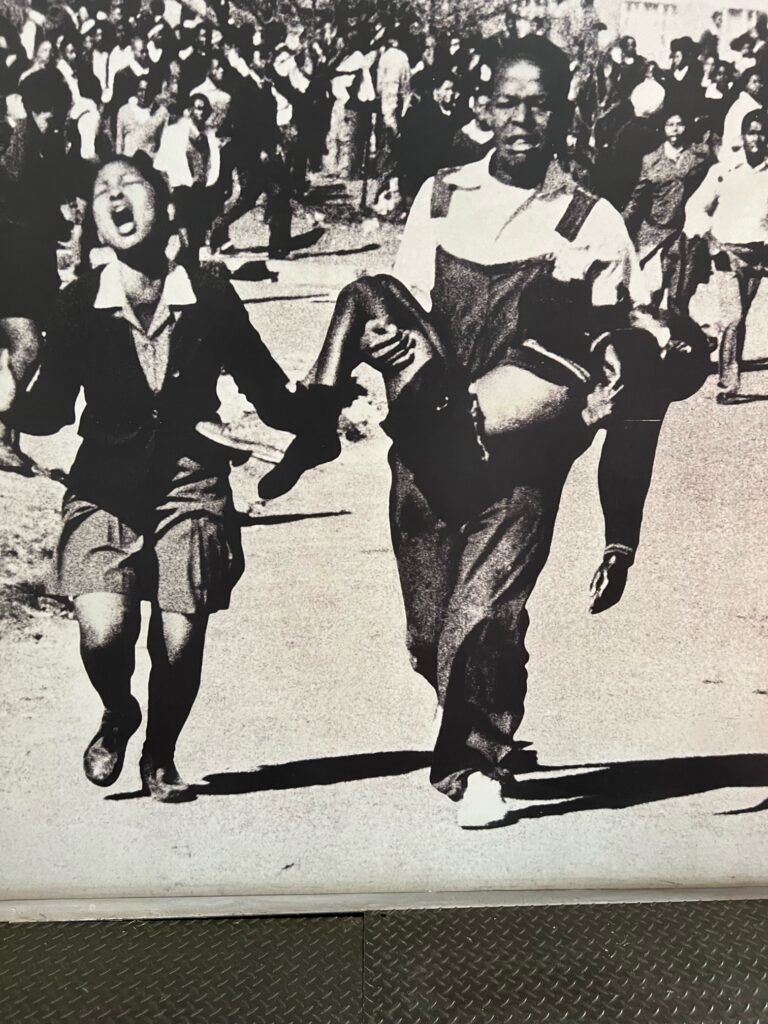

Today, in Johannesburg I visited Soweto township and the Hector Pieterson Museum.

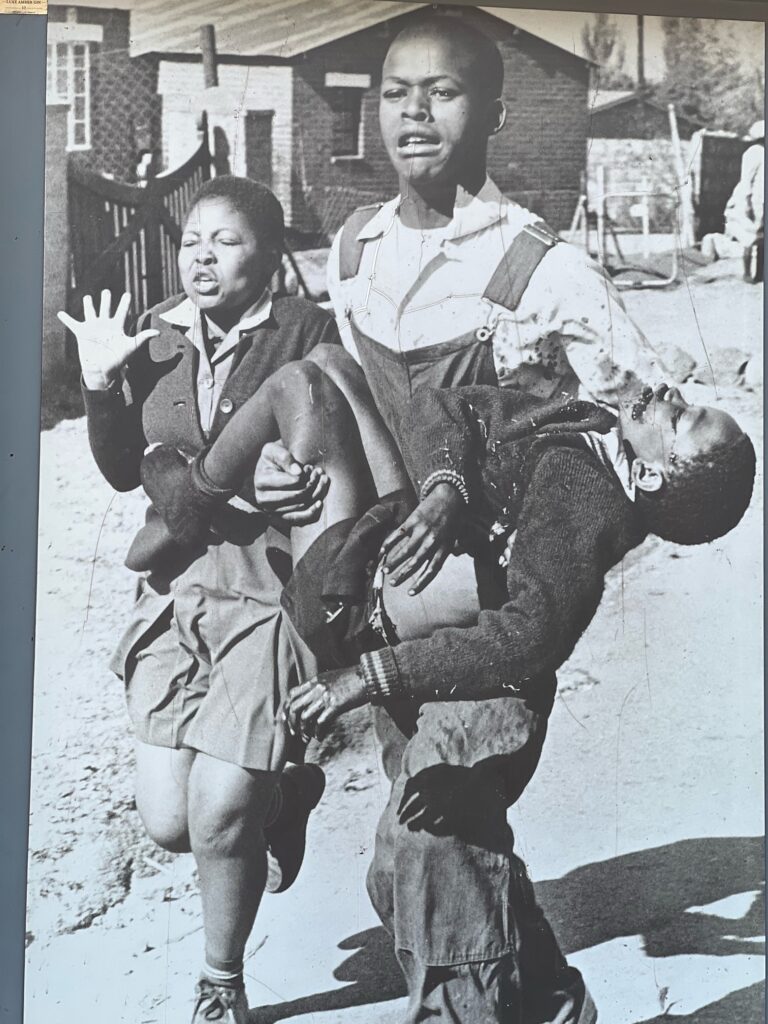

The museum is named for the young boy who was shot and killed by police on June 16, 1976, during the student marches protesting the mandatory use of the Afrikaans language in their schools to the exclusion of their native languages.

I was able to hear a first-hand account of the events of that day by Mama Antoinette, Hector’s older sister who was participating in the march.

On the morning of Wednesday, 16 June, 20,000 students in Soweto assembled in school grounds before beginning their march to Orlando Stadium where a protest against Afrikaans was to be held. On the way, not far from Phefeni Junior Secondary School on Vilikazi Street, 12-year-old Hector Pieterson joined the group which included his older sister Antoinette.

After a brief standoff with police, a shot was fired. Mama Antoinette recalled everyone running. And hiding. She showed us the place she hid and where she saw her brother standing out in the open. She called to him and he made his way to her, but there were more shots and confusion and they were separated. She said that spot is special to her because it was the last place she ever saw her brother alive. There were more shots and Antoinette saw a young man running up the street. She didn’t know what he was doing but then she saw the body he was carrying and recognized the shoes. She followed, crying, asking what he was doing with her brother. They finally arrived at a clinic where a doctor said Hector was dead.

There are famous photographs of that day showing a dying Hector Pieterson, cradled in the arms of a fellow student, with his terrified sister running beside them. These images, taken by news photographer Sam Nzima, became a symbol of the resistance against apartheid. Today, June 16 is commemorated as Youth Day in South Africa.

I asked Mama Antoinette what reconciliation means to her. She said she felt 50/50 pain and hope. She echoed some of what Kgotso told me yesterday. She said only about 15% of white Africans seemed to have any interest in reconciliation but wanted black Africans to just move on and forget the past. She emphasized reconciliation takes two parties, and you can only do your own part.

She was able to take part in the Truth and Reconciliation in 1996 and share her story. At first, she didn’t want to, but realized she needed to in order to free herself of the burden and pain she’d been holding onto for so long. She shared her story and the commission asked if she wanted to know who killed her brother. She had to really think about that but eventually decided no, but she told the commission she forgave everyone. She said she needed to. It wasn’t just for them, but for her, too. She needed release from that moment as the definitive moment of her life. She needed to cut the chains that tied her to that tragedy and the men who shot her brother so she could be truly free. She had to forgive to find peace and finally live a new life. She told me, “we must let the dead rest in peace, but the living must live in peace rather than in pieces.”

She was in pieces until she was able to share her story with the commission and forgive others. There was no other way to wholeness and newness. While reconciliation takes two, forgiveness only takes one. She echoes Tutu’s famous phrase, “There is no future without forgiveness” because she has lived it.

After the museum we walked with Mama Antoinette through Soweto to the house where former South African President Nelson Mandela lived, on and off, for more than 14 years. The house has now become a museum that tells the tale, in sound, film, interpretive panels and guided tours, of the Mandela family during the apartheid era and beyond.

In his landmark autobiography, The Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela describes coming back to his house in Soweto in 1990 upon his release after 27 years in prison: ‘That night I returned with Winnie [his then-wife] to No. 8115 in Orlando West. It was only then that I knew in my heart I had left prison. For me No. 8115 was the centre point of my world, the place marked with an X in my mental geography.’

Vilakazi Street, where the Mandelas lived, is the only street in the world to have housed 2 Nobel laureates − the other being Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

In 1961, Nelson Mandela left No. 8115 for life on the run as a political activist. He was arrested and imprisoned in 1962. I wrote about that after my visit to one of his prisons, Robben Island.

His second wife, Winnie, who he married in 1958, was subjected to harassment, torture and imprisonment while living there on her own with the children.

I can only imagine the terror and struggle and anger that would often fill the house as her daughters had to watch their mother be dragged away by Apartheid police again and agin. This was routinely undertaken from 1962 until 1986, when Winnie returned from exile in Brandfort to continue life with her children. On 28 July 1988, Winnie and Nelson’s house was burnt to the ground by a fire after a conflict between the Mandela United Football Club which Winnie led, and pupils from Daliwonga High School. The community came together to help rebuild the Mandela’s house.

11 years later, on 16 March 1999, the house was awarded the status of a public heritage site, with Nelson Mandela as the Founder Trustee.

I learned a lot about the Mandelas’ lives and struggles at the house. His life was full of difficult circumstances and near impossible choices. What I’ve discovered through these different journeys and experiences is that I can’t judge people for what they do in contexts and situations so vastly different than my own. I can’t judge what an oppressed Irish Republican decides to do as they see they community destroyed by paramilitary groups any more than I can judge Mandela for some of the choices he made in his struggle for freedom for his people, or what people did in our own country from freedom from Britain or their supposed masters. We never know how we’d respond in similar circumstances unless we find ourselves in them. I pray we never do.

So we cannot and should not judge, but be willing to learn from them and their mistakes and successes and failures along the long roads to freedom.

There’s a lot of information out there about Mandela in the form of movies and biographies so I don’t want to rehash a lot of what you can easily find on your own, but here a few highlights that stuck out to me;

Mandela was expelled for joining a student protest while studying at Fort Hare. After a short stint as a security guard at a mine, he spent some time as a legal clerk in the law firm Witkin, Edelman and Sidelsky. His passion and natural aptitude for law was seen through his studies both in and out of prison, and the establishment of South Africa’s first Black law firm, Mandela and Tambo, with Oliver Tambo in August 1952.

His involvement in politics became more pronounced from 1944 when he helped to start the ANC (African National Congress) Youth League. The following years saw harsh punishment from the state against Mandela and his fellow political activists.

Some of the most notable movements in his activist career were leading the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto weSizwe, facing sabotage charges at the Rivonia Trial, and being sentenced to prison and banned from political activity multiple times. These moments led to a life imprisonment sentence in 1964. He was freed from prison in 1990 amid growing domestic and international pressure and fears of racial civil war by President F. W. de Klerk. Mandela was then elected President in 1994.

While there are a lot of opportunities to learn about Nelson, there aren’t as many to learn about his wife Winnie. Winnie was just as intelligent and driven as Nelson, finishing the top of her class for her social work degree in 1955. She chose a medical social worker job opportunity in Johannesburg over a scholarship in the USA. Nelson and Winnie were both charismatic and had a passion for equality and justice for their country and the world.

It must have been extremely difficult for Winnie in those early years (but also while Nelson was in prison). She walked into a life characterized by intense underground campaigning, which frequently meant she and Nelson couldn’t be together. The police raids in the dead of night became a constant feature in the family’s life. The police would raid the home and ransack the place. A few months after finding out about her first pregnancy, Winnie and other women embarked on mass action to protest the Apartheid government’s Pass Laws. She was arrested along with 1000 other women. She was appalled by the inhumane prison conditions. This intensified her resolve to keep fighting for justice and in the subsequent years she was continually harassed and imprisoned.

In 2016, the South African government recognized Winnie for her contributions to the liberation struggle with the award of the Silver Order of Luthuli. After a long illness, she passed on at the age of 81 on April 2, 2018.

While the Mandelas were active in the struggle for justice, they were also leading voices for reconciliation. Reconciliation can’t happen without justice and mercy. Mandela knew there was a divide in his country, a legal divide between races that became economic and philosophical and educational. Life was not good for the oppressed majority and anger was building. He knew there would need to be peace and reconciliation with the minority white Africa in power, but that couldn’t happen before justice was done. He worked for equality and for power-sharing and when that was accomplished he didn’t use his new power to hurt but to help hear the old wounds of his country.

We, too, need to reconcile over many things in our nation, but first we have to ask, has justice been done? Is there more work to do in order to make reconciliation possible? To ask for reconciliation without justice is to ask someone to say all the wrongs done to them are okay and can continue.

This doesn’t mean that justice has to be perfectly done. That’s never the case. No one will ever agree on when justice is complete or done the right way. But if there is no progress, it’s insulting and demeaning to expect reconciliation. It’d be like an abused woman being asked to reconcile with her husband while continuing to be abused and knowing it will continue to happen in the future. We would never suggest that (at least I hope not). The same is true for societies where there has been injustice.