Weekly Article

Rev. Marie Buffaloe • Parish Associate Pastor at Derry Church 1997-2022

July 4, 2024Editor’s Note: On the first Thursday of each month, the eNews feature article highlights the mission focus for the month. In July we’re lifting up elder care and the good work of Christian Churches United of the Tri-County Area.

“Getting old isn’t for sissies!” Okay, I can’t remember when I first heard this, but I think it was at Derry Church. I had just asked an older member that casual question, ‘How are you doing?’ and received a laundry list of aches and pains that ended in his declaration about aging. I remember nodding and trying to imagine that person’s frustrations and aging issues. I don’t need to imagine it any longer: I’m beginning to live it. Maybe you are, too — if not for yourself, perhaps for a spouse, an older parent, grandparent, neighbor, or friend.

Now imagine some of those aging issues without the safety nets of reliable health care or access to needed medications — without a partner, children, or any family who can support you, and not having a home or a safe housing or funds to pay the rent or fuel for heating. Add onto that long list chronic struggles with your mental health. And did I mention there are no retirement funds, or bank account savings? No wonder you can feel like no one cares or even sees you.

One of Derry’s mission commitments is to help provide care to elders, not just for those within the church family, but also for those who are falling between the cracks without anyone noticing. For many years, Derry has been a financial partner with Christian Churches United, which provides care to persons living in Dauphin, Cumberland and Perry counties who live on the streets or who feel helpless to find a safe home. It is a partnership of 100 congregations working with various agencies to support neighbors in need.

In talking with Darrel Reinford, director of CCU, I learned that over one-third of those they assist are over 55 years of age, and that number is growing. Some unhoused persons choose to live on the streets, often in encampments where they make a shelter and even build community. A street outreach team from CCU makes regular contact and coordinates their care with other agencies like Downtown Daily Bread. The Compassion Action Network responds to immediate concerns and provides transportation for free monthly laundry assistance at a local laundromat who donates its service.

The HELP office at CCU provides a comprehensive approach to homelessness and poverty alleviation through crisis resolution, emergency aid, and housing assistance. They provide short-term help through rent assistance, winter fuel assistance, and emergency winter housing. Their rapid rehousing helps to provide security deposits for apartments, case management, and budget counseling.

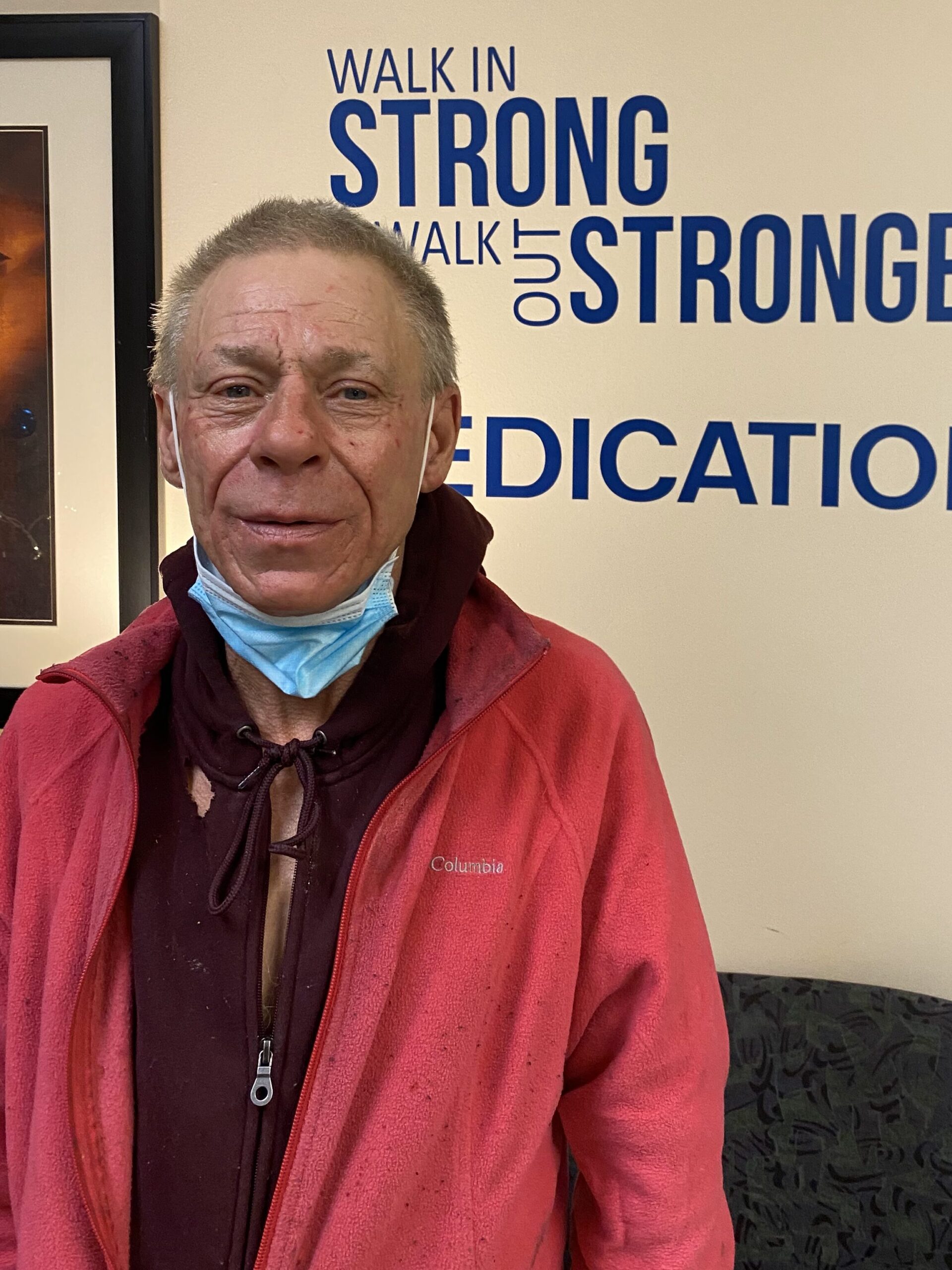

I’ve had a chance to meet some of the men who live at Susquehanna Harbor Safe Haven who are chronically homeless. There they find a safe and caring shelter within a supportive network. Years ago a mission team from Derry helped to paint one of the rooms at this facility. It brings joy to see some of these sincere and often mentally challenged men smile and find a home and a safe haven from the streets. Over half of those who were assisted last year were 55 and older.

This weekend as we reflect on the vision of American forefathers, I am reminded of the final words of the Pledge of Allegiance to our flag as we commit ourselves to “liberty and justice for all.” That hope and vision includes elderly ones in our community who are easily forgotten and overlooked. It’s a good time to revisit those words and our actions.