Author: Susan George

Rev. Matthew Best • Pastor, Christ Lutheran Church, Harrisburg

November 2, 2023A young woman came to the door of Christ Lutheran Church and rang the bell. As I opened the door and greeted her, I could see the expression on her face: she was concerned and looked uncertain. And she was very pregnant. She spoke no English, and my Spanish is limited. Thanks to Google Translate, I was able to discern that she was looking for the medical outreach clinic and she was told that the church could help her. I escorted her to the entrance of the clinic and explained to her in my broken Spanish that she could talk with a nurse who could help her directly. As we entered the lobby which had other people waiting to be seen, I introduced her to the nurses who immediately took her under their wing to offer her care and support.

This is a typical day at Christ Lutheran Church and one of the biggest reasons I wanted to come to here. I serve as pastor of Christ Lutheran Church as well as the executive director of the health ministries. My background includes extensive history in politics and government, entrepreneurial coaching, and at a food pantry. During my previous call, our congregation did a variety of ministries with those who were unhoused and in poverty.

I want to thank Derry Church for being a crucial partner for the Health Ministries at Christ Lutheran Church, going back to 2017. I look forward to seeing that relationship grow and strengthen as we continue helping our neighbors in need.

The Health Ministries at Christ Lutheran Church include a free medical outreach clinic which is visited by an average of 800 people each month with an assortment of health needs. The clinic is staffed by nurses from Penn State Health who offer care and support for every person who enters the clinic. Because of partners like you, Christ Lutheran Church is able to ensure that the clinic has all the supplies it needs including non-prescription medication, bandages, socks and underwear, reader glasses, and more.

We also host a free dental clinic that takes place three times a month. The clinic is staffed by dentists in the area who volunteer their time and expertise, as well as dental assistants who are paid by the church to be onsite for the clinic. The dental clinic sees between 6-12 patients each time it is open, and the main focus is on people who are experiencing active pain, offering fillings as well as tooth extractions. Plans are in the works to expand the dental clinic by moving it to the first floor, which would give us the ability to add an additional chair and be able to see even more patients.

In January, we will be launching our newest clinic which we are calling “Healthy on the Hill.” One of our nurses recently became a Licensed Nurse Practitioner, giving her the ability to prescribe medication as well as refer people for tests. Much of the focus of this clinic will be working with people who have chronic conditions such as diabetes, which require more consistent medical attention and care for the patients’ wellbeing.

Along with these ministries, Christ Lutheran Church also partners with Harrisburg Area Community College. Every nursing and dental hygiene student in their respective programs spends at least one rotation through the clinics at the church. This means that students are getting important hands-on experience that helps shape their career. It’s been reported back to me from the instructors that the students’ time at the Health Ministries of Christ Lutheran Church are some of the most important and formative parts of their education.

Thank you for your partnership in this ministry. We could not do this without you, quite literally. Because of your support, so many people’s lives are positively impacted, and they can start to receive healing. You help make Christ Lutheran Church and the health ministries that happen here a special place of healing. Thank you!

Natalie Taylor • Derry member

October 26, 2023

I am so incredibly lucky to have grown up in Derry Presbyterian Church. The number of opportunities I have been given from when I was in elementary school in Pilgrim Fellowship to now as a college senior have been so numerous. I remember in Pilgrim Fellowship being lucky to have opportunities like going out to the apple orchard together, having lock-ins, and shopping together for our Giving Tree gifts. It was the little gatherings that really showed me God’s love in big ways.

As I got older, I joined Youth Group and started to go on trips! The first trip I ever went on was our Philadelphia missions’ trip in 2017. I was a freshman in high school, and I was very nervous to go on this trip. It was the first time I had ever been on a trip like this on my own. However, that trip opened a door to a new part of my life, traveling and serving. I am so grateful that Derry continued to give us trips to go on after that, like Montreat and Triennium! Each trip has helped me grow in God’s love and show his love to others. Because of these trips I was able to continue my love of serving by going to Poland on a service trip in 2022 and going to Italy this past summer to work with refugees! I am also excited to be able to go on a trip to Ireland next summer to learn about our church and grow in my faith while we’re there.

Derry truly provides so many opportunities to grow and share God’s love, and it’s important to appreciate them and take those opportunities. You may never know the kind of impact it can make in your own life.

Kathy & Ron Hetrick • Derry Members

October 19, 2023

Pastor Stephen asked Ron and me to write this article for the eNews reflecting on how we can relate to the theme “God Gives,” which has been chosen for the Fall stewardship emphasis this year.

Carrying out this request actually gave us the opportunity to stop and reflect on the many many gifts that we have received from God, especially since joining Derry Church in May 2022.

During my lifetime, I have developed a theory that has been proven over and over again. Ron teases me about my commitment to it, but he has seen real results many times…whenever we engaged in acts of “giving to others” (of our time, talents, money or other resources) we have been rewarded many times over in one way or another. I truly believe that God has provided us with our needs (and then some) because we have been among the “givers” of life. [You have heard, I’m sure, that humans are sometimes classified as “givers” or “takers”.] We have come to believe that because God first gave to us… in response, and in trying to follow His example, we give to others – which results in us being rewarded with good feelings and/or positive outcomes in return.

Throughout our lives, God has provided Ron and me with choices to make, which, because of our choices, led us in directions that have been good for us. One of the choices he gave us in 2021 and 2022, was to come to Derry and eventually join this congregation.

We have found that the Derry congregation, as an entity, could definitely be classified as “a giver.” We developed this premise from our very first encounters with the church and its members, and continue to feel this way today, as exemplified by –

The friendliness and genuine caring that we have received from those we encounter at whatever church activity we attend…

The manner in which members (and their friends and family) are prayed for, and provided with visits, prayer shawls, meals, transportation, grief support, and whatever compassionate care is needed and/or appropriate…

The myriad of opportunities provided by the church for individuals to utilize their interests, skills and God-given talents, as well as the utilization of the resources of the congregation to serve others through the diverse programs that Derry has designed to reach out to the community…

The sense of belonging and accomplishment that we have felt by being active with the Sanctuary Choir under the leadership and care of Dan Dorty…

The detailed planning by the staff, and active participation by congregational members, that we have observed, which results in the coordination of every aspect of each worship service to make it flow smoothly and reverently…

The attention paid by the Session members to appropriately carry out the responsibilities of the governing body of this church, particularly in the area of personnel changes and needs…

The passionate dedication to, as well as the resources solicited and committed to, mission projects — which span ages, socioeconomic circumstances, geographic locations and various categories of societal needs… and,

The way in which Pastor Stephen reminds us of our responsibilities to God to carry out God’s plans (for this congregation, our community and this world in general), through our actions and interactions.

At Derry we have observed the congregation’s stated mission in action: God’s word is proclaimed, God’s love is shared, and there is a conscious effort to practice justice in God’s name. In response to what God has given to Derry Church, the extensive programming is the congregation’s gift to each other.

We are thankful that God has given us the opportunity to worship and interact with the members of Derry Church, and by doing so, to “give back to God” by sharing God’s love with others through the many loving efforts of this congregation.

Dick Hann • Derry Member

October 12, 2023

When Elise and I moved back to the Hershey area in the mid 1960s, we were looking for a church home where we could raise our family in a caring church, a place where we could grow our faith through worship, mission, music and the youth program. We found that at Derry and started our journey in 1968.

After several years, I was ordained as an Elder and joined the Worship Committee. In the early 1970s the Vietnam war was a contentious time for the youth and adults. The Worship Committee got the youth involved in plays and musicals starting in 1971. It was expanded with adults and youth, not only from the congregation but the community who participated in plays and full musicals. This was the start of the Vesper Series, which later began ARTS ALIVE! We continue today to praise God through music and the arts with ARTS ALIVE! thanks to the support of our congregation and the community.

Elise and I had a number of opportunities to travel with the Derry travel group over the years. One of the most emotional trips was to Israel, where we had communion at the tomb, walked where Jesus walked, and touched the Jordan river where Jesus was baptized. Another trip was taking a journey in parts of Europe to many of the early biblical sites and tracing how Christianity spread throughout the world. In 1999 we traveled to Northern Ireland, where we traced our Derry heritage and witnessed reconciliation in that area.

We know that all of the programs at Derry require participation and finances. The foundation for my wanting to help others started when I was 10 years old. The church I grew up in was looking for a family to adopt in Germany after WWII and help them to recover. My family adopted a family of five in Germany. Although we were a family of six children, we would send a care package to the family every three months for several years. Still, today I remember that act as forming my future giving ministry.

Over the years Elise and I supported Derry with our time and money as best we could. We filled out the envelopes each week for many years before changing to online giving.

Elise was one who worked behind the scenes. She helped me prepare communion for over 25 years. She cut the bread while I filled the cups, then she would check to see that everything was just right on the communion table.

Elise’s journey at Derry ended earlier this year, but her journey continues with the Lord. We appreciate the caring congregation we have at Derry for the many cards and prayers, and for the choir coming to our home and singing hymns for Elise. We also appreciated the comfort provided by the caring people of Hospice who saw us through this difficult time.

We were blessed to find a church home that provides so many ways to grow our faith — through worship and many programs, and through our strong mission focus locally and around the world.

Jane Robertson • Derry Member

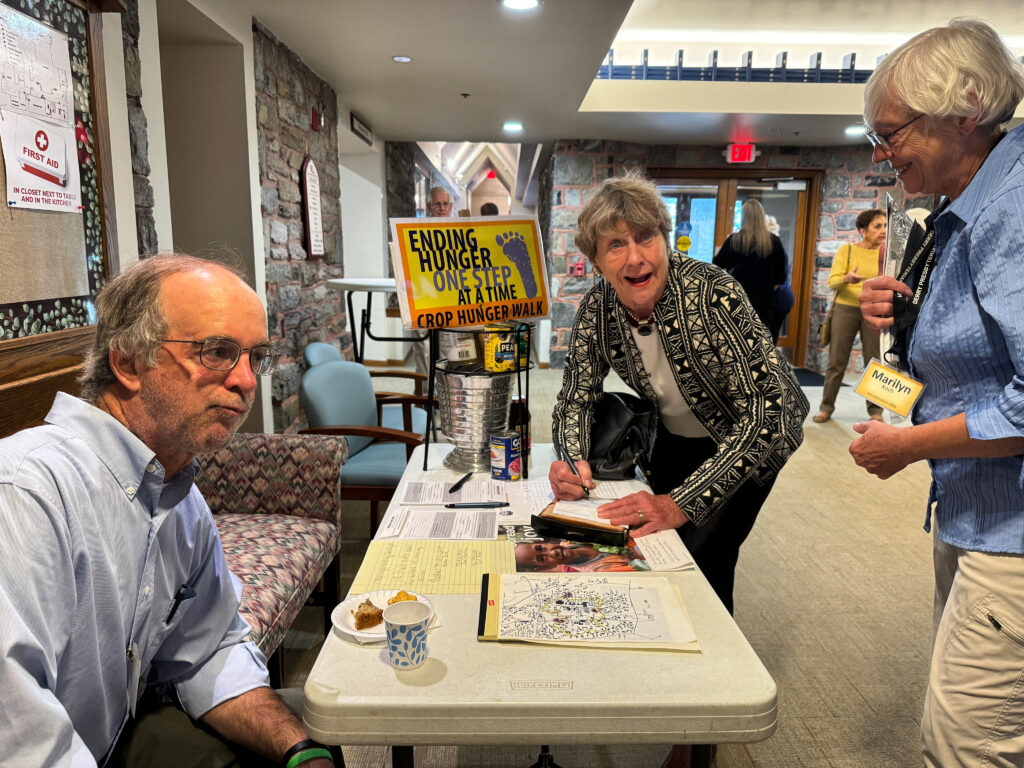

October 5, 2023Editor’s Note: On the first Thursday of each month, the eNews feature article highlights the mission focus for that month. In October we’re lifting up the 2023 CROP Walk, one way we can take action to care for hungry people in our community and around the world. This message written by Jane first appeared as a feature article in the 2011 eNews and is just as relevant today as it was 12 years ago.

Post worship fellowships, Terrific Tuesdays, corn roasts, cookie walks: these are just a few of the food-related events that we enjoy here at Derry Church. We sure do love to eat!

Fortunately for us, food is abundant. But that’s not the case for many people around the globe, as well as here in the United States. Worldwide, over a billion people are hungry – half of them are children. In the U.S. more than 36 million do not get enough to eat.

Sometimes when I hear troubling statistics such as these, I wonder what can I possibly do to make a difference? Perhaps you, too, have had similar thoughts. Well, one thing we can do is to make a commitment to participate in the 38th Annual Hershey/Hummelstown Crop Hunger Walk on Sunday, October 22.

Top reasons why you should support this walk:

- It is great exercise – a lovely 5k walk on the grounds of the Milton Hershey School.

- It is a family- friendly/pet-friendly mission event.

- It is an opportunity to socialize with folks from the community.

- Your donation will help meet our community goal of raising $10,000.

- In past years we’ve had as many as 60 walkers. With your participation, Derry could top that number this year.

- 25% of the money raised stays in our community to support local food banks

- 75% of the money raised is used by Church World Service to feed hungry people around the globe.

AND THE NUMBER ONE REASON YOU SHOULD SUPPORT THIS WALK:

It is the Christian thing to do.

…if you offer your food to the hungry and satisfy the needs of the afflicted, then your light shall rise in the darkness and your gloom be like the noon day.

(Isaiah 58:10)

Ok, now that I have convinced you to participate, here is what you need to know to get started:

- Mark your calendar and join the Walk on Sunday, October 22 at 2 pm on the Milton Hershey School grounds.

- Invite family, friends, and leashed pets to join you.

- Request donations from family, friends, and neighbors.

- Register for the walk online or at the registration table in the Narthex on Oct 8, 15, and 22 between services and after the 10:30 am service. Registration and donations will also be accepted at the CROP Walk. Look for the registration table near the start line.

- Make a donation: you can give online or make checks payable to CWS/CROP.

- Contact Marilyn Koch, Carl Rohr, or me if you have questions.

That’s it. Simple! So mark your calendar, recruit your family and friends, lace up your sneakers, and let’s all help to end hunger – one step at time.

Craig Kegerise • Treasurer

September 28, 2023

We have reached September and are entering a new budgeting season. It is time for the annual update on how the church is doing financially and my projections for the rest of the year.

We started the year in a very strong position with income exceeding budget and expenses well below budget. However, the typical summer downturn hit. In fact, August was the lowest income month in over 10 years. As of the end of August, we have received income contributions that are 61.7% of our budgeted $1,299,000 income and approximately 14% below 2022 contributions. That relates to being $65,635 below budget. However, Y-T-D expenses are $74,278 below budget or 61.2% below the annual budget amount of $1,370,882. As of the end of August, our income-expenses are $8,643 under budget. If our expenses hold and our contributions return to those at the beginning of the year, we should finish the year at budget.

As the Session, the Stewardship & Finance Committee, and other committees look forward to the 2024 budget and the future, we are working to ensure that Derry Church provides for the needs of our church members and the community as well as the financial stability of the church. By planning for the future, we can make sure we are managing our resources responsibly.

Because of the generous support of the congregation, we have not only met our operating costs, but have accomplished many capital projects such as refurbishment of the cemetery walls, improved signage around the church and an improved sound system. We have been able to sponsor and support a refugee family. Because of the generous support of the congregation, a new van was purchased in addition to a fantastic new piano for the sanctuary. We have been able to do mission work in our community and throughout the world, whether it be helping youth with college scholarships or building a new wing on the school in Pakistan.

I would like to thank the congregation for your continued support of the church and its mission work in the community and the world. As our new stewardship campaign, “God Gives” begins, I look forward to the support of the congregation for our ongoing programs and exciting new ventures.

If you have any questions or would like to discuss anything relating to Derry’s finances, please contact me.

Rev. Stephen McKinney-Whitaker • Pastor

September 21, 2023One of the reasons I became a Presbyterian is because Presbyterians take educational mission seriously. The Presbyterian tradition values the importance of helping people to think for themselves so that they can form a relationship with Christ in a unique and personal way.

We are not a tradition that tells people what they must think. Instead, we teach about God and help people learn how faith touches every part of their lives. Christian Education helps us understand who God is and how God is with us and for us. It teaches us God’s better way to live and thrive in this world by being in right relationship with each other and with God as we follow God’s will and ways.

As Presbyterians, we believe that education is part of the ministry of all members, that every person has the duty to be a teacher as well as a learner. When members join Derry, they promise to participate in some form of education. Membership is ministry for all of us, and being a Christian requires the sharing of our faith in God and Jesus Christ wherever we are, through our lifestyle, the way we spend our money or give it away, by living responsibly in our private and public lives, and by deliberately allocating time to make the world a more peaceful, just, and human place.

We are all called to become a beacon of God’s truth, whether we are sharing a meal at home, living out our vocation or avocation, or enjoying life with friends and family. Wherever we find ourselves, we are teaching others about Christ as we provide living lessons about what it means to be beloved children of God and followers of Jesus Christ.

I invite you to take advantage of the educational opportunities at Derry Church to learn more about God, the Bible, the church, and the world that we live in:

11 Minute Lessons: If you don’t have a lot of time, 11 Minute Lessons is a great educational option. Join me in the Chapel after both worship services or watch the videos on Facebook or YouTube. This year we’re going through the books of 1 and 2 Peter verse by verse, 11 minutes at a time.

Sunday School: Classes for all ages meet 9:15-10:15 am. Sunday School is a chance to learn about life together with God and connect with one another. I’m teaching Sunday School for the 6th-12th grade youth this year along with volunteers, and we have a great team leading our children’s classes for Pre-K, K-2nd, and 3rd-5th grades. The adult Issues Class meets in room 7 and is live streamed. A Bible Study class will meet weekly in room 2 beginning Oct 8.

Sunday School is one of the earliest memories children have of church, and these memories can last a lifetime. Will you join our wonderful team of Sunday school teachers who are making a difference in the lives of Derry’s children? Taking a turn once a month or every other month would be a huge help in support of our Christian Education program. Just reach out to M.E. Steelman and let her know your availability.

Tuesday evenings are another opportunity to invest in the children of Derry and participate in their education as they learn stories, express their faith through art, and learn about the history of Derry through the 300th Anniversary book they will be creating together.

Small Group Studies: Choose from groups that meet weekly or monthly:

- A weekly Monday morning group meets at 11 am

- A Thursday group meets at 10:30 am

- Presbyterian Women offer a study on the third Wednesday of the month at 1 pm

- A monthly Monday evening women’s group meets on the first Monday at 7 pm

- A once-a-month Bible study for our Prime Timers meets on Mondays at 12:45 pm

- Men’s Breakfast, which includes devotions, meets on the first Wednesday of the month at 7:30 am

- A Women’s Journey in Faith and Friendship meets twice a month on Sunday evenings

I’d love to add at least one more small group this year. If you are interested in helping start a small group discussion/study group or being a part of a new one, please contact me. I’d be glad to help you get started and suggest some discussion guides or studies to direct your time together.

Education is a gift that no one can take from you. Education has the power to inform and transform our lives. It can help us build stronger relationships with each other and with God. I encourage you to take advantage of Derry’s many educational opportunities as we grow in faith together this year.

Sue George • Director of Communications & Technology

September 14, 2023

I admit there are times it’s hard for me to talk about my faith. I’d like to blame it on my stoic Lutheran upbringing, but I think it’s really because I’m not sure what kind of reaction I’ll get from whoever I’m talking with: what if they give me a funny look or ask me a question I can’t answer? Do I want to put myself out there in that risky way? I know I should, but it can be hard and awkward.

If only there was a way to introduce Derry Church in a non-threatening, easy way.

But wait, now there is!

This summer the Communications & Technology Committee (CTC) partnered with our Vacation Bible School leaders to create a Derry Church tote bag, enough for all the VBS families to have one and to make freely available to everyone in our church family who wants one.

As print advertising opportunities become scarcer, it’s on the CTC to find unique and engaging ways to make the church’s presence known in our community. Why not put our advertising dollars toward a nice item that people will use when they’re out and about? It’s exciting to think that this sturdy, simple bag could be a conversation starter. Or that people will see the bags all over town, in the grocery store or drug store or farmer’s market, and with repetition and familiarity, may think, “I keep seeing those bags. There must be something going on over there at Derry Church. I should check them out.”

If you don’t yet have a bag, I invite you to stop by the welcome table in the Narthex and get one. Don’t leave it in your car: use it on your errands and shopping, and make it visible in your shopping cart. But be prepared: anything could happen, from funny looks to faith questions.

My bag’s ready, and this time I’m not going to wimp out. Bring on the sideways glances and questions: I’m carrying my bag proudly, and I’m glad to be an ambassador for Derry Church.

PS: Later this fall, the CTC will be offering an opportunity to purchase shirts featuring Derry’s tree logo. It’s another way you can be an ambassador for Derry Church, especially as we head into our 300th anniversary year. Keep an eye on the eNews for details.

Dan Dorty • Director of Music and Organist

September 7, 2023Dear Derry Church Family,

As summer comes to a close and fall swiftly approaches, I hope this letter finds you well and you are enjoying these warm days and beautiful blue skies. Where has the time gone? As you may imagine, our August has been chaotic and unpredictable. However, during these past weeks, there has been an overwhelming outpouring of prayers, letters, cards, flowers, offers of meals, and care embracing Sarah and me. Your unwavering spiritual strength and support have touched our hearts beyond what we can put into words. You have surrounded us in love, lifted us up, and encouraged our faith throughout this journey; thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

An update: my medical team has scheduled bypass surgery via laparoscopic robot for October 17 at UPMC Harrisburg. The prognosis is favorable, and recovery is roughly six weeks. My cardiology and transplant teams feel that despite the narrowing in my heart from nearly eight years of dialysis, I will live a long, healthy life after two stents and this upcoming bypass. Praise God, my gratitude to all who have overseen my medical care. In the interim, my cardiothoracic surgeon has cleared me to be back at the organ console and piano, directing and staying active to keep my heart healthy until the 17th. Thank you for your continued prayers throughout these next months.

On August 24, the Sanctuary Choir began rehearsing for the fall season and will sing for the first time on Sunday. Repertoire ranges from well-known hymn arrangements to Mendelssohn’s Verleih uns Frieden (sung in German), Look at the World by John Rutter, and a world premiere of Psalm 13: How Long, O Lord, by composer Yakov Lychik, on September 24. If you’d like to join the Sanctuary Choir for an exciting season of great music, please contact me or speak to any choir member on Sunday mornings following worship!

Terrific Tuesday kicks off next Tuesday, September 12, with dinner beginning at 5 pm in Fellowship Hall, followed by rehearsals for our children’s and youth music and God’s Hidden Hands Puppet ministries. Tuesday evening worship moves to an earlier time, 6:00-6:45 pm in the Chapel. Derry Ringers rehearse in the Music Room from 7:30-8:30 pm, and we need two more ringers to fill out the five-octave choir. If you can read music and are interested, please contact me!

At 4 pm Sunday, September 24, Tyler Canonico, nationally acclaimed organist and Minister of Music and Organist at Market Square Presbyterian Church, and I will present an Arts Alive concert of piano and organ duets in the Sanctuary. The concert will feature works of classical composers, hymn arrangements, and movie music including Pirates of the Caribbean, Harry Potter, and more! Come hear our Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ and Steinway & Sons concert grand piano in action for an afternoon of exciting music!

Christmas at Derry concerts are set for Sunday, December 10 at 2 pm and 5 pm. The concert entitled “Gaudete!” meaning Rejoice, will feature the Sanctuary Choir, Derry Ringers, acclaimed tenor Christyan Seay, lyric coloratura soprano Nina Cline, soloists from Derry Church, orchestra and percussion, with harp, organ, and piano accompaniment. Join us as we paint the scene of the manger, bright shining star, wise men from afar, and angels singing on high as Mary and Joseph adore the newborn babe, wrapped in cloth and lying in a manger!

As we look forward to this exciting season ahead, I ask for your prayers for a speedy recovery and for God’s healing hand to be upon me. Once again, thank you for your love and unending prayers; words may never fully express my gratitude.

Yours,

Dan

Caitlin Nelson • Executive Liaison, YWCA Greater Harrisburg

August 31, 2023Editor’s Note: On the first Thursday of each month (or close to it), the eNews feature article highlights the mission focus for the month. In September we’re lifting up the Peace & Global Witness Offering, and YWCA Greater Harrisburg, the organization that will receive a portion of the funds collected through this special offering of the Presbyterian Church (USA).

The YWCA Greater Harrisburg’s vision of creating a just community for all began 130 years ago. As the role and the needs of women adapted over time. The YWCA has historically expanded its impact, becoming a driving force that transforms lives.

We embrace a cultural commitment to our core values, through our leadership staff and volunteers, exhibiting respect, accountability, and inclusiveness. We are dedicated to eliminating racism, empowering women, and promoting peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all.

Founded in 1883 to create a safe place for young working women to live and gather, the YWCA Greater Harrisburg focuses on five general program areas:

- Housing and homelessness

- Violence intervention and prevention

- Legal and family visitation

- Children and youth

- Employment readiness and support.

In its 130-year history, the YWCA Greater Harrisburg has maintained its dedication to the provision of quality programs and services that meet the needs of women and families. Providing service to individuals living in Dauphin, Cumberland, and Perry Counties, the YWCA actively serves as an advocate and resource to the community.

The YWCA is working as the crossroads of society’s most pressing issues. We are providing critical health and safety needs by housing and case managing hundreds of individuals who may otherwise end up in emergency rooms. We are providing court accompaniments, so our victims receive justice. We are operating a full-time daycare to provide individuals the ability to return to work.

We are doing this work through the lens of our vision, mission, and purpose. The YWCA is on a mission to eliminate racism and empower women. We work at the intersection of gender, race, age, ethnicity, and orientation.

Today, we combine programming and advocacy to generate institutional, systemic and individual change, by impacting one life at a time.

M.E. Steelman • Director of Church Life and Connection

August 24, 2023The start of a new program year is exciting in so many ways, especially here at the church. The month of September will have our building buzzing with excitement as we welcome everyone back to our classrooms, small group gatherings, and fellowship opportunities. I have no doubt that God’s presence will be felt by all as we continue to prepare for and enjoy the start of another program year at Derry Church.

Not only will the life of the church feel more vibrant with the program year getting under way, you’ll likely feel the rest of your life coming alive as everyone moves away from the slower pace that summer typically brings. So how do you choose what to join, how to fit in, and where to find information on church life and programming? Read on for answers to some of those questions.

What types of programs can I expect?

Derry’s planning teams are working hard to provide a variety of learning and gathering opportunities for Sunday mornings and throughout the week for all ages to enjoy. Sunday mornings this fall will include Sunday School for all ages, choir rehearsal, and 11-Minute Lessons.

Throughout the week we offer a variety of small groups studies so that you can find a group that fits your schedule. You can find fellowship on Monday afternoons, Tuesday evenings and Sundays after worship as we offer opportunities for church and community members. Tuesday evenings include delicious hot dinners in Fellowship Hall for all to enjoy, music and creative arts for our children & youth (preschool-12th grade), and worship in the Chapel.

How can I learn more about all of the different programs Derry Church offers?

The best resource is our church eNewsletter. We try to include all that is happening in this weekly publication. We have also been adding the schedule to the Sunday bulletin and have printed copies of the eNews available on the information desk in the Narthex.

If you are looking for information specific to youth, contact Pastor Stephen. For children, email me and ask to be added to the regular newsletters we share with all that is happening for these specific age groups.

Why is it important for me to be involved in more than Sunday worship?

Growing your faith is a lifelong journey. Our faith experiences become greater and more meaningful when we gather with others to learn, share, wrestle and prepare for the ups and downs of life. Gathering for worship can help us feel ready to face the start of a week with new thoughts and good intentions. But often life can quickly overtake those thoughts and intentions, and before we know it we are sitting in worship again and realizing we haven’t invited God to join us throughout the week. There are also times when life’s ups and downs will leave us needing or craving help and care from our church friend. Derry’s various programs are not only created for learning and sharing, they are designed to help us strengthen our relationships with one another.

How do I get involved?

Simple: come! Whether you are a parent who wants to help your children or youth grow their faith, or you are an adult looking to challenge and explore your faith, or you are looking for connections with others, all of our programs are designed to welcome you when you are able to join us. I encourage you to step out from the craziness or loneliness of life and carve out time to explore your faith and grow your relationship with God and with your church family.

What if I’m just too busy right now?

We all go through seasons of life when time works against us and keeps us from being able to be more involved. That does not mean our faith journey needs to be put on pause or moved to the back burner. We can still explore our faith. Over the last few weeks, we have begun to include faith questions in the bulletin and eNews and at the start of staff and committee meetings. These questions are designed to help us pause and reflect as we spend a few minutes with ourselves to discover how God is finding us in our daily lives. Questions can be answered while sitting alone, sitting in worship, or talked about at church and family gatherings. We hope they spark something within you that allows you to open your heart and mind even more.

What if I have questions about Derry’s various programs or want more information about how to get involved?

Please call (717-533-9667), send an email, stop by the church office, or talk with our staff members on Sundays to learn more about any of our church programs and how you can get involoved.

I look forward to seeing you soon!

Beckie Freiberg • Faith Community Nurse

August 17, 2023

On May 14 I had the honor of being commissioned as Derry’s first Faith Community Nurse. What an exciting day! I had always dreamed of doing some sort of health ministry with my nursing skills, and now I’m on my way.

Many of you may be wondering about the role of a Faith Community Nurse (FCN). What are her responsibilities? How can she help me?

A FCN Is a subset of nursing like pediatrics, medical surgical, women’s health, cardiovascular care, and more. This speciality is subject to its own Scope and Standards of Practice and is required to adhere to these standards including confidentiality. I will soon be taking an extensive course for FCN and will receive my certification.

A FCN works within a faith community and incorporates health, wellness, and spirituality into her practice. I can do this by teaching about different health topics, teaching and encouraging wellness practices, acting as a resource person, and incorporating spirituality into these teachings. I can also help you navigate today’s complex healthcare systems. In my role as a FCN, I can provide counsel on a variety of issues and help to seek solutions, and offer a listening ear. Home and long term care facilities visits, hospital visits, as well as phone calls and follow-up calls after surgery are also a part of my duties. If you need community resources, I can help guide you to those services.

I can review medications with you and make suggestions on how to take them. Nursing assessments of different situations are also part of my role. If you have a health question, I can help with that and I can do some health assessments and screening tests, such as take blood pressures and offer advice. Some of the things that I cannot do are hands-on nursing care (things like basic physical care or placing meds into containers for ease of remembering to take them).

At Derry, I am partnering with the new Health and Wellness Committee, using their knowledge to act as a health and wellness guide for our church family. “Health Time with Nurse Beckie” is a new educational program I’m offering on Zoom on the fourth Wednesday of each month. Join me as I present a health topic followed by discussion and questions. The first session is Wednesday, August 23 at 1 pm. I’ll be talking about ticks and lyme disease. Click this link to join the conversation.

I am very excited about this new role at Derry Church and I look forward to meeting each and every one of you and getting to know you. Please reach out with your suggestions and any questions. I’m happy to take calls and make visits. You can contact me through the church office (717-533-9667) or reach out by email: care@derrypres.org.

I feel so blessed that God and Derry Church have called me to this ministry, and I thank you for the opportunity to serve this congregation.