Author: Susan George

Pam Whitenack • Chair, Derry 300 Committee

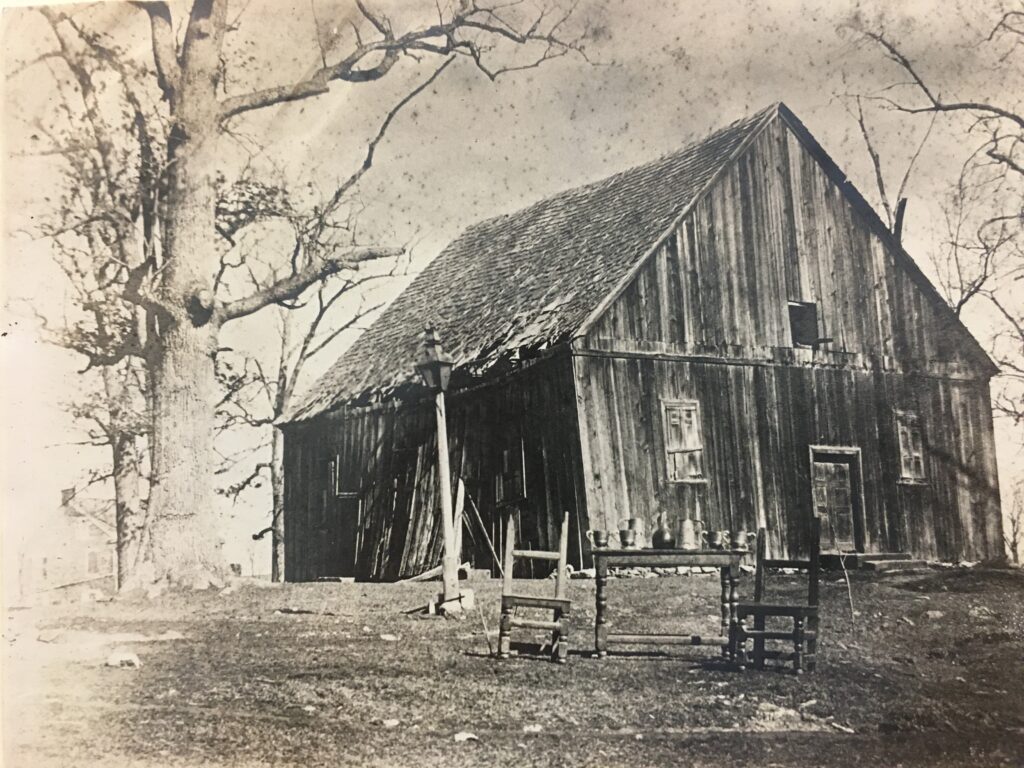

July 25, 2024The last pastor called to serve Derry Church in the 19th century was Reverend Andrew Mitchell. He served both Derry and Paxton Churches, with Paxton receiving two-thirds of his time and Derry one-third. Mitchell left Derry in 1874 to take a commission as a United States Army Chaplain. Following his departure, few worship services were held and the church building, “Old Derry,” began to fall into ruin.

Old Derry Church

By the early 1880s Derry Church was on the brink of collapse. Membership had dwindled to a handful and there had not been resources to support the hiring of a pastor or maintaining the church property for over a decade.

It was largely due to the efforts of two women that the Derry Church Chapel was erected. Mrs. Charles Bailey of Harrisburg, a descendant of the original founders, became interested in reviving the church at Derry. She succeeded in interesting Mrs. Dawson Coleman of Lebanon in this goal. Given the fact that there were only six or seven members and no pastor, this was a bold undertaking.

The efforts of these two women led to a circular addressed to all local and regional Presbyterian families that might be interested in preserving Derry Church. It was distributed in 1882. This document was signed by A. Boyd Hamilton, Thomas H. Robinson, William H. Egle, John Logan, and Samuel A. Martin. With the exception of John Logan, these men were not members of Derry Church, but were prominent Presbyterians in the region.

This awakened an interest and culminated in establishing a committee to pursue restoring Derry Church. The committee issued the following charter outlining the group’s goals:

CHARTER:

It has been decided to restore, or if that is found impossible, erect a proper Memorial Chapel fitted for preaching, as a Mission Station, at the Presbyterian Church of “Derry” in Derry Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Some substantial aid has been promised toward this tribute to the departed fathers and mothers who founded the congregation more than 150 years ago.

It is thought fitting that the descendants of those who are interred in the Grave Yard, or were members of the Church, should be asked to contribute toward this worthy object in such amounts as they may choose, and remit to the custodian of the fund. Persons who have no such motive for contributing have promised assistance. In this combination we hope to find success. The object is so praiseworthy that no such thing as a failure would be thought of. The work contemplated will not be expensive, and will be of so substantial a character as not to require further expense for another hundred years. The neglect of this beautiful and hallowed spot in the past 20 years has been shameful, and for the credit of the Presbyterian name it should be put and kept in repair. There is also in the growing community about Derry a rapidly enlarging field for Christian enterprise, and prospect of reviving this decayed congregation.

Treasurer, A. Boyd Hamilton

William K. Alricks, Esq.

Thomas H. Robinson

William H. Egle

John Logan

Samuel A. Martin

While the committee investigated repairing and restoring the old building, ultimately it was decided that the cost was too much. In May 1883, “Old Derry” was demolished and the church’s records were moved to the Paxton Presbyterian Church manse for safe-keeping.

On Monday, April 23, 1883, a meeting was held at the church to discuss future plans.

People from Harrisburg, Lebanon, and the surrounding region attended, including John Logan, 83 years old and the last surviving trustee of the old congregation. At the meeting new Trustees were elected: A. Boyd Hamilton, President, Horace Brock, Secretary and William R. Alricks, Treasurer. A resolution was passed ‘that a church building shall be erected.’

A. Boyd Hamilton, a member of Market Square Presbyterian Church and a founding member of the Dauphin County Historical Society, led the effort to establish a building committee for a new sanctuary. The estimated cost was $7,000. The building committee included Mrs. Emma H. Bailey of Harrisburg, Mr. and Mrs. Horace Brock of Lebanon, and Mr. A. Boyd Hamilton.

Plans were made to build the new memorial Chapel from blue limestone, and to place it on the same location as the demolished Old Derry Church building. The new structure would be substantial: 50 feet deep, the front 30 feet wide and the rear 44 feet, allowing space for the pulpit and an east transept. The bell tower would measure 52 feet high, and 10 feet square. Plans for the new building called for the transept to serve as a classroom, with two additional classrooms available in the basement beneath the chapel. The Chapel would seat 125 people.

On October 2, 1884, the cornerstone was laid. By then, only the first floor of the new church building had been constructed. No windows had been installed, and a temporary floor and seating were placed for those participating in the service.

Descendants of early parishioners and pastors were contacted from far and wide. Many attended the ceremonies, while many more contributed to the project. A. Boyd Hamilton presided over the ceremony. John W. Simonton, presiding judge of the Dauphin County Court and a charter member of the Dauphin County Historical Society, offered the opening Address, and William H. Egle, a noted Harrisburg physician and Pennsylvania historian, offered a Historical Address. Reverend Samuel Martin of Lebanon preached the sermon, and the cornerstone was laid by direct descendants of Reverend John Elder.

The building was completed in late 1886. Fundraising was sometimes slow, resulting in construction delays. On January 6, 1887, Derry dedicated its new Chapel at its 11 am worship service. The original Chapel included the west transept, and a furnace room and classrooms in the lower level. The east transept, outer vestibule, and additional classrooms would not be added until the 1935 expansion.

The Chapel’s stained glass windows were given in memory of former pastors and elders of the church. Some of the windows were the gifts of descendants, and others were donated by area Sunday Schools, including Market Square and Pine Street Presbyterian Church Sunday Schools (Harrisburg), Christ Church Sunday School (Lebanon), York Presbyterian Church Sunday School, Grace Chapel Sunday School (Racetown), James Coleman Sunday School (Cornwall), and the Lancaster Presbyterian Church Sunday School. Most of the windows recognized one the pastors who had served Derry between 1732 and 1874 and two were dedicated to former Derry Church members who had served as Elders. The local Derry Church Village also contributed towards the construction of the Chapel. The window, fitted into the arch over the main entrance, reads “A thank offering from Derry Village.”

While the steps to build the Chapel didn’t always go smoothly, members and friends believed, hoped and persevered to ensure Derry’s future.

C. Richard Carty • Derry 300 Committee Member

July 18, 2024

On the 50th anniversary of Derry Church’s Sunday School program (1933), past and present superintendents pose for this photo. Standing, l-r: Ivan L. Mease (1920-1934), Simon P. Bacastow (1916-1917), Robert S. Woomer (1918-1920), Irving L. Reist (1911-1915), Wilmer W. Steele (1917-1918); seated, l-r: Dr. EEB Sheaffer (1888-1891), Mrs. Elizabeth F. Hershey (1898-1899), George H. Seiler (1883-1887).

Growing up in a Methodist church in Chambersburg, Sunday School was an expected and regular part of every week. There never was a question of whether or not I would attend. While I looked forward to it each week, as a child and even as an adult, I never thought about how or where Sunday School began.

We must transport ourselves to industrial England in the late 1700s to find the beginnings of Sunday school, when city dwellers were working long hours in dangerous and unhealthy conditions. Skilled and unskilled workers labored six days a week, often ten to 12 hours daily. Children as young as eight often worked alongside their parents in hazardous conditions.

There were no publicly funded schools because education was considered a family responsibility. If you were poor, you were likely illiterate, impoverished, and perhaps a threat to society. On Sunday, children ran wild in the city streets, often breaking windows and robbing homes. Enduring horrendous working conditions during the week, many street urchins learned to be pickpockets and thieves.

While it is possible to find numerous examples of men and women gathering children together for religious instruction, the Sunday School movement began with Robert Raikes, a wealthy newspaper publisher in Gloucester, England.

According to journalist Tracy Early, “Deciding they [the children] would be better off learning to read and receiving guidance in proper behavior, he (Raikes) hired a teacher and set up a school that met on their free day and would thereby “get the urchins off the street.”

While it was not without opposition and setbacks, the movement soon spread beyond Gloucester. Raikes and others believed in “school on Sundays for these poor children where good Christian people would teach them to read and write, teach them the Ten Commandments, and instruct them in moral living. Maybe with a basic education, they could escape their dreadful life.” Raikes made teaching materials such as the Ten Commandments and other verses from Scripture, primers, spellers, reading books and catechism books available free of charge. Later they were paid for by donations from supporters.

The movement spread when spiritual and intellectual philanthropists read newspaper articles about Sunday schools, and by 1785 250,000 children in Britain attended these schools. For most, it was their only formal education, where they learned to read and write by using the Bible as their textbook.

The Sunday school movement was cross-denominational and open to children and adults. A typical day would offer literacy and arithmetic lessons from ten to two, then there would be an hour lunch break followed by church and catechism lessons until 5:30 pm. Religious education was a core component.

Sunday school unions formed throughout Great Britain, and eventually sent missionaries around the world. At first these organizations were interdenominational, then evolved to become denominational. There was strong opposition to women taking on a leadership role in the movement, yet young women played an important role in the movement by raising money to fund the education of young children in Britain and worldwide.

The Sunday School idea spread, taking root in America. By 1832, there were more than 8,000 Sunday Schools. By 1875, there were more than 65,000 schools and by 1889, there were ten million children in American Sunday Schools that were performing the heavy task of public education, sponsored by Christians out of their own pockets.

The idea of education was so powerful that governments soon got into the act. Compulsory public schools emerged in America to teach the three R’s, thus leaving the handling of religion to churches, especially among those Protestants without parochial schools. As public education spread, churches devoted Sunday school time to moral and spiritual training. The American Sunday school movement took its structure from developments in public schools, developing age appropriate curriculums and organizing classes by age.

We know very little about the early years of Derry Church’s Sunday School as most of the church’s early records were destroyed in a fire in 1894. After Rev. Mitchell resigned in 1874, Derry Church did not hold any worship services until 1883. That year, the building was demolished when it was deemed unsafe.

In spite of these obstacles, a small group of Derry members persevered. Even though they were without a church building or a pastor, the remaining members banded together to establish the Derry Church Sunday School in 1883. They reached out to George H Seiler of Swatara Station, then engaged in state Sunday school work. He was elected superintendent and trained lay people to conduct classes for adults and children. A member loaned his portable pump organ and his daughter played so that there would be music to accompany hymns during Sunday School worship. For classroom space, a L-shaped wing was added to the Session House. This enlarged space was also used to hold worship services until the Chapel was completed in 1887.

While church membership was small, the Sunday School grew rapidly and class size averaged 60 students each week. Adult classes were added as interest increased. The Derry Church Sunday School sustained the church and helped it grow. Following Seiler’s tenure as superintendent, many other people led a robust Sunday school program of education and worship. The national Sunday school program provided a curriculum used by many Protestant denominations including Derry.

By 1909, Derry had consistent pastoral leadership that encouraged a growing membership and helped expand the Sunday school program. By 1934, Sunday School enrollment had reached almost 200 students with an average weekly attendance of 146 people. In addition to classes, Sunday school included a modified worship experience often including music. As enrollment grew, more classrooms were needed. In 1935 and again in 1951, Derry Church expanded, adding more classrooms and fellowship space. Derry’s Sunday School continued to steadily expand through the next several decades. By 1968, enrollment reached 447 students.

During these decades, Derry Church Sunday School operated almost independent of the larger church, with its own leadership and budget. In addition to funding the purchase of curriculum and supplies, each year funds from Sunday School collections were earmarked for benevolence to both foreign and national charitable organizations such as the Presbyterian Home in Newville, war relief during World War II, and Camp Michaux, a church camp. Derry Church Sunday School also made donations to support the Building Fund as the church undertook new construction projects.

Beginning in the early 1970s, the Derry Church Sunday School began to be incorporated into the larger mission of the church. The Sunday school budget was incorporated into the church’s annual budget and a new staff position, Director of Christian Education, was created.

In 1971, Derry Church hired its first professional Christian educator, Nancy Joiner [Reinert]. By then, the Sunday School had grown to include classes for individual grade levels along with numerous adult classes. Derry had just purchased a new comprehensive curriculum created by the national church. Ms. Joiner’s first task was to educate and guide Derry’s Sunday school teachers in implementing the new curriculum.

Nancy’s leadership established a robust program of youth engagement, ranging from youth groups for many ages, to creating opportunities for performing drama and music. Derry’s future growth in a music ministry was made possible by the hiring of the church’s first full time Director of Music, Herb Fowler. While Derry’s Sunday School had always included learning hymns as a part of Sunday school worship services, now music education and ministry became an integral part of Derry’s mission.

Nancy Joiner Reinert resigned in 1975 following the birth of her first child. Recognizing the importance of providing Christian Education leadership, Derry Church continued to hire full-time Directors of Christian Education, including Betsy Terry (1975-1978), Susan Eshbach (1978-1979), Cheryl Galan (1979-1984), Betty Bates (1984-1989), Candice Reid (1992-1993), and Debbie Hough (1994-2018). Debbie came to Derry Church with extensive experience in Christian education. She led a program that reached all ages, making Christian education a vital part of our ministry, mission, and worship. She created curriculums that connected popular culture and themes with Christianity, encouraged lay teachers and learners to find themselves in God’s story, and established an annual Theological Forum that brought noted Biblical and theological scholars. This commitment to Christian Education continues under the leadership of Rev. Shawn Gray, Associate Pastor of Christian Education.

In addition to Sunday classes, Derry’s Christian Education program now includes several Bible study groups, a Tuesday evening Creative Arts program, Vacation Bible School, fellowship opportunities for children and youth, KIWI [Kids In Worship Instruction], a Children & Sacraments class, God’s Hidden Hands puppet ministry, and the Derry Discovery Days preschool.

For over 140 years, Derry Presbyterian Church has supported Christian education for children and adults. As we celebrate our 300th anniversary, the opportunities for growth and new direction of our Christian Education programs are limitless.

For further reading:

Larsen, Tim. When Did Sunday Schools Start? Christianity Today, March 2024. https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/2008/august/when-did-sunday-schools-start.html

Lynn, Robert L. and Wright, Elliott, The Big Little School—200 years of the Sunday School, (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1971)

Phillips, Douglas W. The History of the Sunday School Movement. Audio CD; The Vision

Forum, Amazon Books 9781933431352

Early, Tracy. “Another Bicentennial: The Sunday School Movement” The Christian Science Monitor, June 2, 1980,

Short History of the Sunday School, compiled by students in Keith Drury’s “Local Church Education” course at Indiana Wesleyan University over the years 1996-2010

Youth Travel Reflections

July 11, 2024Introduction from Pastor Stephen:

Corrymeela’s purpose is to help people learn to live well together. I think our 13 youth and four adults did that this past week during our time at Corrymeela in Northern Ireland, through our programs, our tours, our experiences, and the fun we had together.

We learned more about ourselves and others through games, exercises, and programs designed to help us explore communication, conflict, hard conversations, and divisions. We engaged with the history of Ireland and learned more about The Troubles. We led worship together at First Derry Presbyterian Church.

I enjoyed all we did, but it was most rewarding to see all these youths connect and reconnect with each other. We laughed so much every day, and all the youth pushed themselves outside their comfort zones — whether that was dancing with the group at night, sharing more about themselves and their thoughts, or asking someone for the Wifi password.

Each night we gathered to share what we learned that day and what we’ll always remember. There were lessons learned and memories made that, I hope, will last our whole lives long.

I asked the youth to think about why this trip was important and meaningful to them, and what some of their main takeaways were. Here are some of their responses:

This trip helped me recontextualize conflict and helped me compare the conflict in my life and my environment to the conflict that we learned about in Northern Ireland. I learned ways that the Northern Ireland troubles were resolved, and how these methods can be used in my life.

I appreciated the trip because it helped me learn more about humanity. Because we had so many different people, it was cool to observe how they experienced the trip. Mostly, I learned about myself, and how incomplete I currently am.

The trip was meaningful to me because it was my first time out of the country, which was so amazing! I also was able to reconnect with people I grew up with, which was especially meaningful to me.

This trip was really meaningful and important to me because it’s my last trip as a “Derry youth.” It was really great to reconnect with everyone that I have known since we were in elementary school and to explore a new place together! I truly will cherish this trip forever.

I really enjoyed this trip because I got to talk to and get to know people that I haven’t seen in a while. This trip was meaningful to me because I got to go to another country for the first time. I will take away the dance parties and fun games we played and discussions that we had.

I think that I’ll take away the things we did as a group. All the memories we made while hanging out with each other will stick with me forever.

This has been an incredibly meaningful trip to me for so many different reasons. I not only got to travel to a foreign country and had my first plane ride, but I got the opportunity to strengthen relationships with people who I haven’t had the opportunity to be with recently. I will take away all the memories from our trip!

The trip was important to me because I was able to continue to build on relationships and learn about the Ulster-Scot language which I will be incorporating into my everyday vocabulary. I will always remember the times we shared as a group on our walks and at Corrymeela. Ireland is such a beautiful country with an interesting history, so this trip is something I will never forget.

This trip was great because it was my first time in Europe, and it was with a lot of people I haven’t been around much since college started. Learning the church’s history while also having fun hanging out, swimming, and dancing with everyone will make me remember this trip forever.

This was a very meaningful trip to me because I was able to try new things and get out of my comfort zone. I will always remember the landscape while Joey, Stephen, and I golfed in Ballycastle.

This trip was meaningful to me because traveling here to Europe and getting out of America and exploring more things than what I’m used to, has been a wonderful experience. I really enjoyed traveling with this amazing group and will cherish this forever.

Coming to Ireland was extremely meaningful to me because of the fact that I was able to have this opportunity to go to Europe at a convenient cost and learn so much. I was also able to be with all the youth I grew up with and laugh with every single one of them. I will take away the history of conflict we learned that took place in Ireland, all the naturalistic sites we saw, and always having fun with everyone — whether it was in The Dell View doing dance parties and late-night hangouts, or just reflecting on the iconic moments.

This trip was special because I got to know the older youth better and realized how much fun they truly are. I will take away that we should be kind and helpful to others because you never know what they may be going through. I also will take away that we should enjoy every bit of life as best as we can.

I think this trip will forever be a meaningful church and life memory for everyone on it. This trip was made possible by your generous donations to our Empower Youth Fund. I want you all to know this trip was fundamentally about relationships and learning to live well together. I believe our time in Ireland helped us all strengthen relationships and be better citizens of the world.

The youth will share more of what they experienced and learned at our Youth Sunday service in the fall. Thank you for investing in our youth and making this trip possible for everyone.

Rev. Marie Buffaloe • Parish Associate Pastor at Derry Church 1997-2022

July 4, 2024Editor’s Note: On the first Thursday of each month, the eNews feature article highlights the mission focus for the month. In July we’re lifting up elder care and the good work of Christian Churches United of the Tri-County Area.

“Getting old isn’t for sissies!” Okay, I can’t remember when I first heard this, but I think it was at Derry Church. I had just asked an older member that casual question, ‘How are you doing?’ and received a laundry list of aches and pains that ended in his declaration about aging. I remember nodding and trying to imagine that person’s frustrations and aging issues. I don’t need to imagine it any longer: I’m beginning to live it. Maybe you are, too — if not for yourself, perhaps for a spouse, an older parent, grandparent, neighbor, or friend.

Now imagine some of those aging issues without the safety nets of reliable health care or access to needed medications — without a partner, children, or any family who can support you, and not having a home or a safe housing or funds to pay the rent or fuel for heating. Add onto that long list chronic struggles with your mental health. And did I mention there are no retirement funds, or bank account savings? No wonder you can feel like no one cares or even sees you.

One of Derry’s mission commitments is to help provide care to elders, not just for those within the church family, but also for those who are falling between the cracks without anyone noticing. For many years, Derry has been a financial partner with Christian Churches United, which provides care to persons living in Dauphin, Cumberland and Perry counties who live on the streets or who feel helpless to find a safe home. It is a partnership of 100 congregations working with various agencies to support neighbors in need.

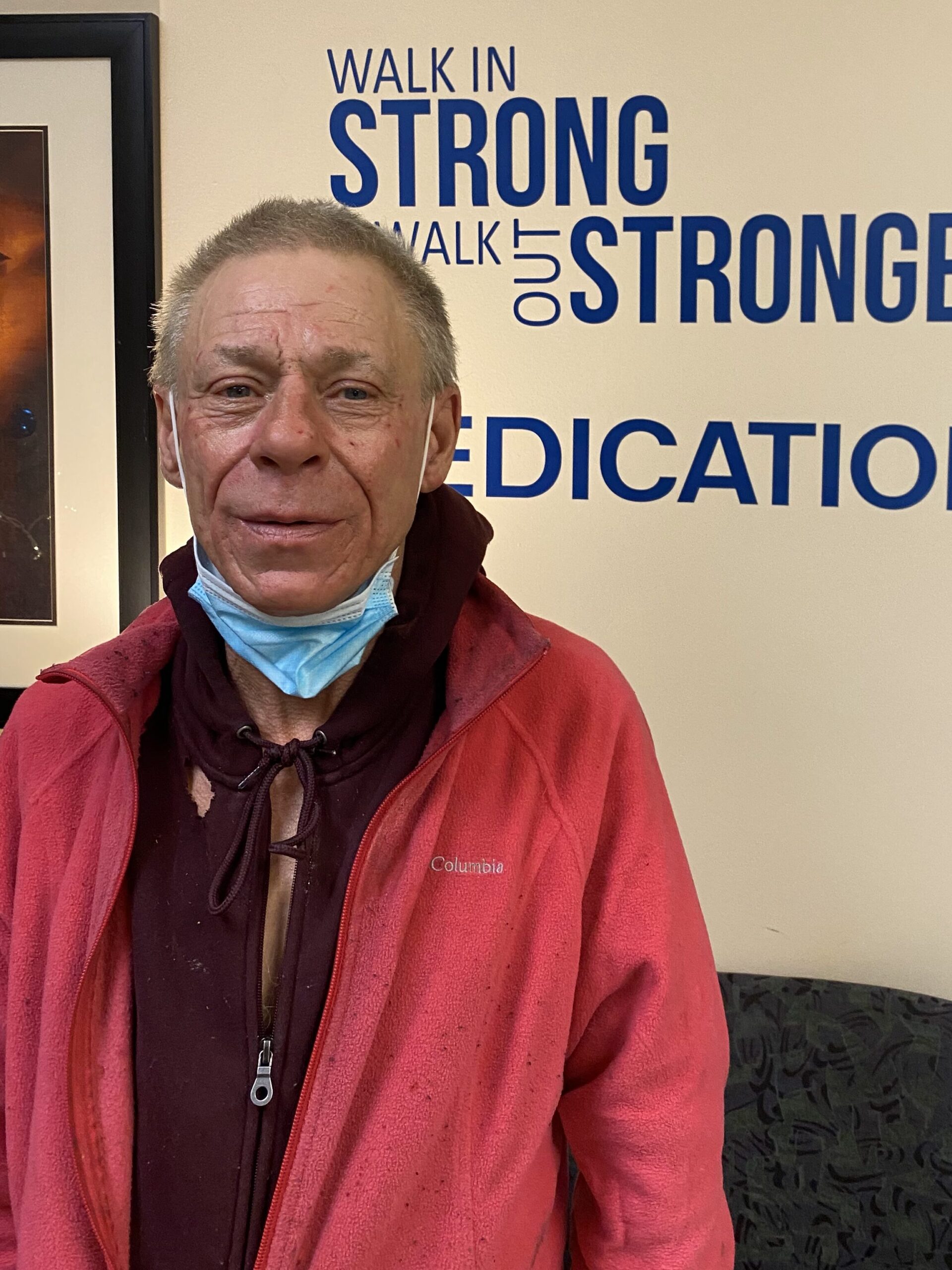

In talking with Darrel Reinford, director of CCU, I learned that over one-third of those they assist are over 55 years of age, and that number is growing. Some unhoused persons choose to live on the streets, often in encampments where they make a shelter and even build community. A street outreach team from CCU makes regular contact and coordinates their care with other agencies like Downtown Daily Bread. The Compassion Action Network responds to immediate concerns and provides transportation for free monthly laundry assistance at a local laundromat who donates its service.

The HELP office at CCU provides a comprehensive approach to homelessness and poverty alleviation through crisis resolution, emergency aid, and housing assistance. They provide short-term help through rent assistance, winter fuel assistance, and emergency winter housing. Their rapid rehousing helps to provide security deposits for apartments, case management, and budget counseling.

I’ve had a chance to meet some of the men who live at Susquehanna Harbor Safe Haven who are chronically homeless. There they find a safe and caring shelter within a supportive network. Years ago a mission team from Derry helped to paint one of the rooms at this facility. It brings joy to see some of these sincere and often mentally challenged men smile and find a home and a safe haven from the streets. Over half of those who were assisted last year were 55 and older.

This weekend as we reflect on the vision of American forefathers, I am reminded of the final words of the Pledge of Allegiance to our flag as we commit ourselves to “liberty and justice for all.” That hope and vision includes elderly ones in our community who are easily forgotten and overlooked. It’s a good time to revisit those words and our actions.

Laura Cox • Director, Derry Discovery Days Preschool

June 27, 2024

Derry Discovery Days preschool wrapped up a busy and exciting year at the end of May!

A special highlight of the year included hosting two family-focused events that involved fundraising components. The first event was our Stride and Ride Fall Festival in late September at Patriot’s Park. Students collected donations from family and friends and biked and scootered all around the park’s loop. It was a lovely morning of fellowship and fun!

Our second event was a Pancakes and Pajamas breakfast in January where families had a delicious breakfast made by the Bartz and Farbaniec families, played games, decorated cookies and participated in a silent auction featuring items donated by many local businesses including the Hershey Country Club, Sweet Velvet Macarons, Where the Wild Things Play and many more!

The success of both of these fundraisers helped DDD purchase a new slide for the playground that was installed in April The structure features a double slide, climbing opportunities and provides hours of fun.

Another wonderful addition to the playground was the addition of the Nature Kitchen, built by Adele Hosenfeld as part of her Eagle Scout project. The kitchen allows children to use their imagination to create culinary creations with leaves, rocks, acorns and items found throughout the playground. Thank you, Adele, for your creativity and craftsmanship!

We are so grateful for all of the love our teaching staff provided to our students. Our teachers provide a warm, nurturing environment and make learning fun. We are truly blessed to have the best staff and we look forward to welcoming back our students for the 2024-25 school year on September 3!

Rev. Shawn Gray • Associate Pastor of Christian Education

June 20, 2024

Last week I had the opportunity and privilege to venture to the Dominican Republic with Derry Church. This trip is organized by Bridges for Community, a non-profit that has had connections to Derry Church from its inception. We were partnered with a group from Morgan Stanley that was comprised of mostly young professionals who worked in AI, investment banking, algorithms, and more. We also had a wonderful range of belief systems represented: agnostic, atheist, Church of Latter Day Saints, Jewish, Catholic, Muslim, and Presbyterian. Many in the group were first and second generation immigrants. This led to hours of conversation where we shared our stories and created new ones together. This group was driven, sharing a common goal to do the most good possible. Bridges helped to direct this energy into tangible results. Over the course of the week, we built three houses from concrete and block, each one about 400 square feet.

Bridges for Community is a secular, non-profit organization that attempts to aid impoverished communities in the DR in the areas of housing, education, and health. The impact they have is dependent on how many people make the trip. Their model is simple in that nearly all the money raised goes directly into the community. They have eight consistent staff members (two from the US and six in the DR). They contract out all the cooking, masons, construction, cleaning, and laundry needs to the people in the local villages. They buy all supplies from local vendors. This helps the local economy in the communities that we are serving.

Bridges has built 53 houses for communities since 2018, and while there is still a need, this has created momentum and energy from within the community. While we were shoveling and mixing cement, people from the village walked up, grabbed a shovel, and helped. I later found out that these were often recipients of houses previously built, or they are related to someone who received help. Their help was much appreciated. What we could do in our boots, gloves, and hats, was often doubled by the locals wearing crocs and using their bare hands.

I was impressed by this organization and have seen firsthand how being a consistent presence that offers aid through a relationship that offers dignity can truly make a difference. While there is still much to do, this community can thrive, and it is amazing that Derry Church through Bridges of Community gets to be a part of that. We had five from Derry go this year. I hope that next year we can double that number.

Courtney McKinney-Whitaker • Derry Member

June 13, 2024

Because most of our historical records were lost in a fire at the end of the 19th century, we know very little about Derry Church during this time. What is clear is that during the 19th century, Derry endured a period of significant decline. There are a variety of probable causes: many of the traditionally Presbyterian and ever peripatetic Scots-Irish moved on from the area, seeking new lands to the south and west, and the ethnic character of the area became increasingly German. Those who remained nearby may have abandoned Presbyterianism, a denomination still focused on formal religious education and entrenched in polity, for the more exciting Methodist and Baptist revivals of the Second Great Awakening, as those denominations came to dominate the American religious landscape.

After Rev. Nathaniel Snowden left Derry and Paxton in 1796, Derry Church struggled to keep a pastor for another decade. In 1799, Rev. Joshua A. Williams accepted a call to Derry and Paxton, but he departed for another position only three years later. Derry then called Rev. James Adair, who died before his installation. Not until 1807 did Derry and Paxton extend a call to the Rev. James Russell Sharon, but it seems to have been worth the wait. Rev. Sharon served both churches for 36 years, until his death in 1843. At that point, Derry and Paxton called the Rev. Albert Marshal Boggs, who served from 1844-1847 before resigning from the ministry. Following a three-year vacancy, the Rev. Andrew Dinsmore Mitchell served Derry and Paxton for the quarter-century from 1850-1874, when he resigned to become an army chaplain.

Derry Township remained a rural farming community until the 20th century. However, in the early 19th century the Horseshoe and Reading Turnpikes (now known as State Roads 322 and 422) and the Union Canal linked the area to the wider world, providing transportation for farm goods and raw materials such as lumber and limestone. Most significant for Derry Church was the arrival of the Lebanon Valley Railroad in 1858 as the tracks passed uncomfortably close to Derry’s cemetery. The wooden topper on the cemetery wall had to be removed due to the frequency of catching fire from railroad sparks!

Even as church membership declined, the community grew. The one-room schoolhouse now on Mansion Road was built in 1844 to serve the village of Derry Church, an area encompassing around one to two miles from the church. It was the first one-room schoolhouse in Derry Township, and it operated until 1904. (Six-year-old Milton Hershey attended school there during the winter of 1863-64.) From 1858 to about 1900, Derry Church rented the Session House to the community of Derry Church for use as a post office.

By 1883, only a few members remained at Derry Church, and the 1769 building known as “Old Derry” was dangerously unstable and had to be torn down. Luckily, community organizations such as the Dauphin County Historical Society and the Harrisburg Historical Society, as well as descendants of early members, recognized Derry’s historical significance as one of the earliest churches in the area and stepped in with $7,000 to build a stone chapel. Other area churches donated money for the stained glass windows, which honor Derry’s early ministers.

As funds were raised over time, the Chapel was built over the course of four years and dedicated in 1887. The original Memorial Chapel consisted of a sanctuary with a chancel, a west transept used by the choir and Sunday School, and a bell tower. The chapel still contains some items from Old Derry, including the Lord’s Table and two chairs. The 1831 pulpit hangs on the wall of the east transept in our sanctuary, and we continue to use the pewter communion set originally purchased for use at Old Derry.

The 19th century was nearly fatal for Derry Church. Most of the original founders and their descendants had moved on, and the church building itself was crumbling. But a time of renewed energy and church life was coming. In some respects, Derry Church died and was reborn at the end of the 19th century, and the true ancestors of the church we know today are those who built the stone chapel and breathed new life into Derry during the Sunday School movement, which you will read about in next month’s article.

Pete Feil • Derry Member

June 6, 2024

Just over two months ago, Derry concluded its collection of the One Great Hour of Sharing Offering (OGHS), exceeding the goal of $19,000 by more than $1,000. At Derry, this offering is shared equally with the Presbyterian Church USA (PCUSA) and Bridges to Community (BTC). You might ask, who is BTC? In our 300th anniversary year, what is the history of the connection between BTC and Derry and how has this played out over the years?

The story begins with Derry member, the late Dr. Jack Hewlett. Jack’s cousin, Rev. Bill Daniel, was a Presbyterian pastor who had a project called SWAP (Stop Wasting Abandoned Property) which was rehabbing burned-out rowhomes in Yonkers, NY. A mission project began in the late 1980s with Rev. Daniel and many people at Derry. SWAP quickly became Sweat With a Presbyterian in the Derry vernacular! Many of the people moving into the rehabbed apartments were from Central America. In the early 1990s, Rev. Daniel decided to move to Nicaragua to see if he could help improve their living conditions. He was joined there by another Presbyterian pastor in a series of public works projects, which then developed into the organization known as Bridges to Community. Derry maintained contact with Rev. Daniel and BTC projects over the years. In fact, Derry helped buy a white Kia truck for BTC use.

Fast forward to the turn of the century. Derry’s Mission & Peace Committee (M&P) was looking to establish a long-term, international mission partnership. The Committee established guidelines for mission trips to include participation by the entire congregation, yet realizing not everyone would be able to go, for one reason or another. Those going on a trip would be responsible for the costs of transportation and room and board: these would not be Derry subsidized vacations! Other costs, such as those for administration and construction, would be covered by various fundraising projects, such as currently with the shared OGHS Offering. Remarkedly, no funds from the M&P budget have been used to support a trip. It has all been via trip participants and this congregation’s generous support!

In 2001, Derry reconnected with Rev. Daniel and BTC in Nicaragua, helping to build homes following the destructive effects of Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and an earthquake in 2000. As we left the airport, our luggage was loaded into a white Kia truck! Among the suitcases were several containing Bible school supplies. From the very beginning with SWAP in Yonkers to today, Bible school activities have been an integral part of Derry’s mission trips. Many thanks to Claudia Holtzman for organizing and directing these activities over the years.

Derry’s trips to Nicaragua continued annually through 2017, after which they were curtailed by political unrest. BTC was operating a similar program in the Dominican Republic, so we were able to go there for two years until halted by Covid. The lack of trips almost brought an end to BTC’s mission, but they have come back strong and we have rejoined them for the past two years. Through the years we have been impressed by the BTC model for helping. A local committee decides who will receive a new home. The home is built with local masons, supported by the family and neighbors, and volunteers. There is a payback period by the family, which goes into the local community fund and whose leaders then decide how to further assist community needs.

PCUSA uses the OGHS Offering in three ways: Presbyterian Disaster Assistance, Self-Development of People, and the Presbyterian Hunger Program. The effects of a new home through BTC offer similar results. What does a homeowner get? A new home with securable doors and windows, safe from the elements and theft. We have seen new businesses like stores and a bakery being run out of new homes. This is an agricultural area where many homes are adjacent to the fields which provide food for the family and a source of income. What do they get? The fellowship and knowledge that there are Christians from the United States who care enough to help them build a better quality of life.

Now you know the origins of Bridges to Community and its historic connection to Derry for over 35 years. Thank you for your continued prayers and financial support for this ongoing mission project.

Claire Folts • Children’s Music Director

May 30, 2024

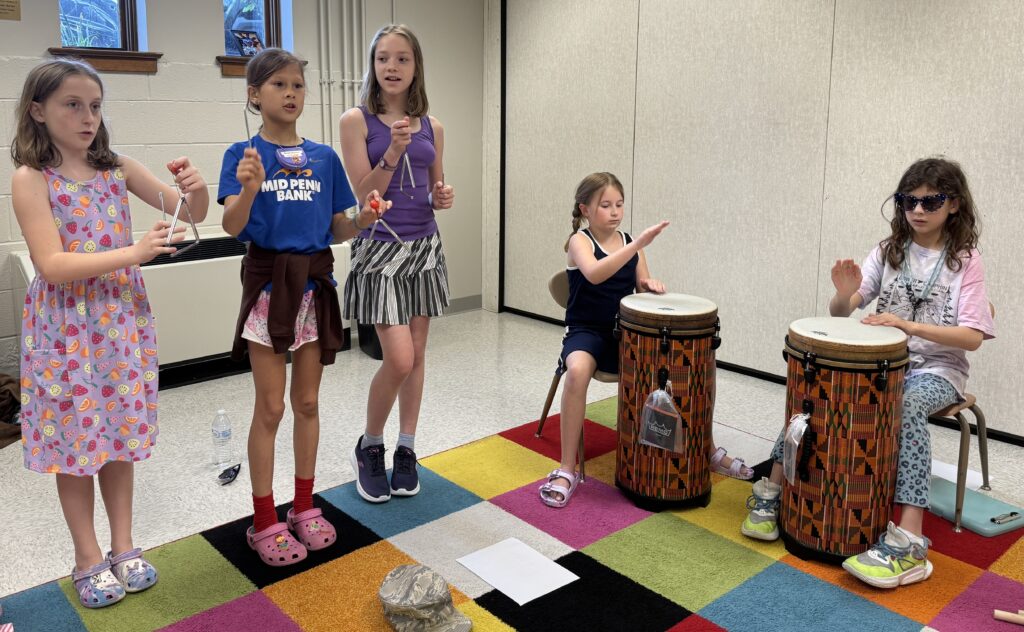

This spring the kids have been playing DRUMS! Just before Christmas, the Children’s Music Program received a gift in memory of Elaine Barner from Lauren and Pieter Daems of a Remo World Music Drumming package. It included 15 tubanos (large standing drums like djembes but easier for kids to play), talking drums, buffalo drums, guiros, cow bells, maracas, sand blocks, claves, and more. All of my kids from preschool up through 5th grade have been having an absolute ball using all of the instruments. So have I!

The preschool children use sand blocks to make the sound of a chugging train as we sing “Get on Board Little Children” and chant “Engine, Engine Number Nine.” The K-2nd grade children used tubanos for the sound of apples hitting the ground and claves and triangles to “say the words without our voices.” Finally, both in Sunday School and on Tuesday nights the 3rd-5th grade children have used a variety of instruments to help tell stories. In fact, you will hear them tell Psalm 66 using words and percussion instruments this Sunday, June 2. I love the chance to incorporate percussion into the children’s music program. Percussion highlights the importance of listening, it’s a way to make music when singing is scary, and quite simply drums are fun!

When playing percussion, listening is key. Drum circles are composed largely of call and response meaning one person leads and the rest answer. You must listen to the lead to be sure you answer logically. If you aren’t listening to each other, you probably aren’t playing together, and it likely sounds like one very loud mess! You have to listen to make sure you line up and sound, as I tell my K-2nd graders, like “one giant drum.”

Singing can be scary for children and adults. Particularly in our K-2nd grade group, we have children who are very nervous to sing. They are NOT nervous to play drums! I love having an option for those kids to make music. As they grow more comfortable in our group, perhaps they will join us in singing and perhaps they won’t. Either way, they are welcome and I’m glad they are part of our musical community.

Even for the kids who love to sing, drums are an incredibly fun addition to our Tuesday evening activities. If you have ever poked your head into room 5 on a Tuesday night between 5:45 and 7:00 pm, you heard a lot of noise and saw a lot of smiles! Many of those smiles were from playing percussion. No matter what your age, you cannot help but smile when playing the drums.

In our children’s music program, the kids are learning to listen, they have found spaces where they feel confident and safe, and they are having fun. I love that they love being here. I look forward to continuing to make music with the kids in the fall!

Bonnie Bowman • Derry Member

May 23, 2024On Thursday, April 11, 44 members of Derry boarded a bus in the church parking lot and departed for a two week tour of Scotland and Ireland. I was very excited as I had never been to either country before and had always hoped to visit them and experience the culture.

We began our journey in Edinburgh at St. Giles Cathedral, which is celebrating its 900th anniversary (making Derry seem young in comparison)! We also attended church at St. Giles the first Sunday of our trip. Each day was filled with historic sites and opportunities to learn more about the landscape and the people.

Scotland and Ireland are breathtaking in their physical beauty. As we traveled by bus and ferry, I was overwhelmed by the views out our window. From a rainbow nestling across the foot of a mountain, to the landscapes seen from many of the castles we visited, every day was a feast for the eyes. I particularly enjoyed the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is a geological wonder with over 40,000 interlocking basalt columns that was formed over the last 60 million years by the cooling and shrinking of lava flows.

As we visited Belfast and Derry, we learned a great deal about the “Troubles”, that period in the latter half of the twentieth century when Ireland was in great turmoil. I learned that the tension stretched back centuries. We visited the walls erected in Belfast and Derry (some of our group even left words of encouragement in the graffiti on the wall) and participated in tours that gave perspective from both sides of the conflict. We were fortunate to meet Rev. David Latimer, a former pastor of First Derry Presbyterian in Northern Ireland, who worked to establish better relations with

both sides of the conflict.

So many of our travels were rooted in our faith and the history of our ancestors. The weather didn’t cooperate on the day the full group was to go to Iona. However, Pastor Stephen managed to put together an excursion the next day for some folks to forego the planned activities and visit on our own. I was fortunate enough to be part of that group. Iona felt to me like a truly holy place. The history and the souls who have worshiped in that beautiful, isolated place seemed palpable to me. I would love to return one day and spend more time there.

Another special day was our visit to our sister congregation in Derry. The people there were so gracious and welcoming. The ladies of the church had a reception before the service with tea and scones (some of the best I’ve ever tasted) and it was such a pleasure meeting and getting to spend time with them. After the service, there was a luncheon just for us at the Guild Hall where we were greeted by the mayor.

I’m a relatively new member at Derry. I joined the choir when I joined the church and have made many friends in their ranks. One of my favorite aspects of the trip was getting to know more members of our church. Every meal and every activity, members of our group spent time socializing, sharing and worshiping together. The sense of community was real and made me so glad to be a member of such a vibrant, caring congregation.

The trip was everything I hoped for and more and I’m so happy to have been a part of it.

Courtney McKinney-Whitaker • Derry member

May 16, 2024Three Churches, One Story

During the 18th century, three major Presbyterian congregations grew along the Swatara. While they squabbled among themselves from time to time, such as during the Old Light-New Light controversy of the Great Awakening, there was more to unite the Derry, Paxton, and Hanover churches than to separate them. Scots-Irish immigrants tended to travel and settle in family groups, and these congregations were united by strong ties of blood, culture, and religion. Many congregants worshiped at two or even three of these churches at various points in their lives. Others might worship at one and be buried at another. Often, the same pastor served more than one church. The lives and histories of these congregations were entwined, so it is helpful to think of the era of the American Revolution and early republic as one story involving three churches.

The Hanover Resolves

By the time the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776, the American Revolution had been raging for over a year. The Declaration’s unprecedented accomplishment was to unite 13 of Great Britain’s North American colonies behind the cause of American independence, but its actual content owed much to ideas expressed across the colonies in preceding years. Prior to the Declaration, many local documents also detailed grievances against the government and declared a willingness to fight for a new relationship with Great Britain. The most well-known of these are the Hanover Resolves adopted in Hanover County, Virginia on July 20, 1774 and the Mecklenburg Resolves adopted in Charlotte, North Carolina on May 31, 1775.

However, the less famous Hanover Resolves likely produced at or near Hanover Presbyterian Church (in what is now East Hanover Township) predate both of these and were the first set of such resolves adopted in Pennsylvania. Adopted on June 4, 1774, the Hanover Resolves contained five points:

1st. That the recent action of the Parliament of Great Britain is iniquitous and oppressive.

2nd. That it is the bounden duty of the people to oppose every measure which tends to deprive them of their just prerogatives.

3rd. That in a closer union of the colonies lies the safeguard of the liberties of the people.

4th. That in the event of Great Britain attempting to force unjust laws upon us by the strength of arms, our cause we leave to heaven and our rifles.

5th. That a committee of nine be appointed, who shall act for us and in our behalf as emergencies may require.

In committing their cause “to heaven and our rifles,” a sentiment in the spirit of the militant theology of John Knox, signers reinforced the ideals of the Scottish Reformation. One member of the Committee for the Hanover Resolves, (later Colonel) John Rodgers, is buried at Derry, and several others are known or thought to be buried at Paxton or Hanover.

A Presbyterian War

During the American Revolution, Scots-Irish Presbyterians fought heavily on the side of the new United States, whether as militia troops, as frontier rangers, or as part of the regular Continental army. British-allied individuals from common mercenary soldiers to King George III himself noted the Presbyterian nature of the rebellion, though at the time they used the term Presbyterian to encompass many groups of dissenters from the Church of England. Presbyterian most commonly referred to the Congregationalists and Puritans of New England and the Scots-Irish Presbyterians of the mid-Atlantic, whose ancestors had given the Crown so much trouble during the 1600s.

The following is a representative sample of sources laying the war at the feet of Presbyterians:

- One Hessian mercenary serving in the British Army wrote home to Germany, “call it not an American Revolution, it is nothing more nor less than an Irish-Scotch Presbyterian Rebellion.”

- A Pennsylvania loyalist said, “that the whole was nothing but a scheme of a parcel of hot-headed Presbyterians.”

- In 1776, advisor William Jones warned the Crown, “this has been a Presbyterian war from the beginning.”

Given these circumstances, it is worth asking to what extent the American Revolution was an extension of the half-century of religious warfare that gripped the island of Great Britain from 1650-1700. Historian Richard Gardiner claims, “Religious and denominational dynamics were vitally central to the revolt. Historians have failed to state this as clearly as it deserves. The allegation that the American Revolution was a Presbyterian rebellion is an important one to understand if we are to have a truly comprehensive understanding of what happened and why…\ the American Revolution did have a ‘holy war’ dynamic to it that pitted Anglicans against dissenters (who were generally referred to as Presbyterians), and in the minds of the loyalists, the war was fundamentally, at bottom, a Presbyterian rebellion.”

Derry’s cemetery plaque lists 40 men who provided military service in the American Revolution. By the late 1780s, Derry Church’s congregation, drawn from up to ten miles from the church, numbered about 40 financially contributing families with at least 70 families in the congregation as a whole, while Derry Township’s full population stood at about 200. Forty men, therefore, indicates a significant portion of the population, and that number leaves out the unknown contributions of women, children, and unenlisted men.

Similar memorial plaques at Paxton and Hanover list several dozen men each. There is some overlap among names on the three memorial plaques, which may indicate separate individuals with the same name, or confusion about some veterans’ final resting places. Either way, it is another indication of the close bonds among these congregations in the 18th century.

After the War

Major military operations ended at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, and the Treaty of Paris officially ended the war in 1783. Dauphin County was carved out of Lancaster County in 1785, its French name an anomaly in a largely Scots-Irish and German area. Most likely, the new county was named to honor French support for the American Revolution, as le Dauphin is the traditional title of the Crown Prince of France.

Reverend John Elder continued to serve Derry and Paxton Churches from 1775 to his retirement in 1791. (Upon his death in 1792, Elder was buried at Paxton.) From 1791-1793, stated supply pastors served Derry and Paxton. In 1793, Derry, Paxton, and Harrisburg (now Market Square) churches called the 23-year-old Reverend Nathaniel Snowden, the first of Derry’s pastors to be born in North America. (Hanover, by this time, appears to have been defunct or in significant decline, though a building remained on the site until 1875.)

It is always challenging to follow a long-established pastor such as John Elder, even when the pastor doesn’t have Elder’s significant sway over civic and political, as well as religious, life. Snowden appears to have struggled with the demands of three churches, and he parted ways with Derry and Paxton in 1796, remaining at Harrisburg/Market Square. While Snowden asked to be relieved only of his responsibilities to Derry, Paxton chose to end their relationship with Snowden as well, leaving him only the city church. Perhaps this is another indication of the strong ties between Derry and Paxton. For another century, until 1895, Paxton and Derry continued to be served by many of the same pastors. Thus, old relationships endured in a new nation.

Sources

Derry Presbyterian Church. In Memory of Heroes of the Revolutionary War and Defenders of the Frontier. 2006. Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Gardiner, Richard. “The Presbyterian Rebellion?” Journal of the American Revolution, September 5, 2013. https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/09/presbyterian-rebellion/.

Harrisburg Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution. In Memory of the Heroes of the Revolution, Frontier Defenders and Soldiers of the French and Indian War Buried in Paxton Churchyard. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Harris Ferry Chapter Sons of the American Revolution. In memory of the 44 veterans of the American Revolution who lie buried here. 1999. Grantville, Pennsylvania.

“Reverend Nathaniel Randolph Snowden (1770-1850).” Church Timeline. Derry Presbyterian Church (USA). 2024.

https://www.derrypres.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Snowden_Nathanial_edited.docx.pdf.

Notes

[i] Capt. Johann Heinrichs to the Counsellor of the Court, January 18, 1778: “Extracts from the Letter Book of Captain Johann Heinrichs of the Hessian Jager Corps, 1778-1780,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 22 (1898), 137. Qtd. in Gardiner.

[ii] “Minutes of the Committee of Safety of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1774-1776,” from the original in the library of General William Watts Hart Davis, Doylestown, Pennsylvania; entry for August 21, 1775, in Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 15 (1891), 266. Qtd. in Gardiner.

[iii] William Jones, “An Address to the British Government on a Subject of Present Concern, 1776,” The Theological, Philosophical and Miscellaneous Works of the Rev. William Jones, 12 vols. (London, 1801), Vol. 12, 356. Qtd. in Gardiner.

Dan Dorty • Director of Music and Organist

May 9, 2024Reflecting on this past year, a feeling of deep gratitude overwhelms me as I reminisce about the many ways God has blessed our music ministry here at Derry Church. Music is essential in our worship, uniting our voices and connecting our hearts as we pray, sing, and hear God’s word read and proclaimed.

Our choirs have had a busy year of music-making with two concerts in addition to preparing and presenting in Sunday worship. Our Christmas at Derry concerts were a success and wouldn’t have been possible without Susan Shuey stepping in during my recovery and helping to conduct. My deepest gratitude to Sue and all of the members of our choirs for coming together and rising to the occasion to present two fantastic Christmas concerts in preparation for a glorious Advent and Christmas season.

In March, we celebrated our 300th anniversary with a Festival of Hymns. The Sanctuary Choir, Derry Ringers, and orchestra presented the hymns of faith to a full house under the direction of acclaimed conductor Linda Tedford. Working with and learning from Linda was a joy as she brought passion and new life to these beloved hymn texts that we deeply cherish.

Our children’s music ministry is growing under the direction of Claire Folts, Director of Children’s Music, and Debbi Kees-Folts, Director of the Celebration Ringers. Our little ones have enjoyed making music together with new percussion instruments given by Lauren and Pieter Daems in memory of Lauren’s mother, Elaine Barner. This set includes Tubanos (African-style tuned drums), Talking Drums, Maracas, Guiros, and many more auxiliary percussion instruments.

Working with our youth on Tuesday evenings is a thrill as we rehearse and learn new music each week to present in worship. If you know of a high school student who likes to sing or play an instrument, we meet on Tuesday evenings at 6:45 pm in the Chapel. Join us!

We will rejoice with voices lifted in singing on Music Sunday, June 2. We’ll have one service at 10:30 am in the Sanctuary, where each of our choirs will share their talents in praise to God as we celebrate the gift of song in worship. Following the service, the congregation will enjoy fellowship at the annual Derry Church picnic on the front lawn.

As Music Sunday is the close of our program year, the choirs will have a break for the summer until they return after the Labor Day weekend. There will be two opportunities to join the Sanctuary Choir for an open loft Sunday. You don’t have to be a great singer, just come to the rehearsal at 9 am and learn an easy anthem to sing at the 10:30 am service. Open loft Sundays are June 30 and August 11. Come and sing!

Summer special music will begin on Sunday, June 9 with members of Derry Church and the surrounding community sharing their many gifts for praise and adoration given to God. Highlights include vocalists and instrumentalists of Derry, a quartet from the Susquehanna Chorale, mezzo-soprano Amy Yovanovich, soprano Victoria Lang, and flute and cello duo Victoria Visceglia and Ali Koch.

We are incredibly blessed at Derry to have so many musicians willingly sharing their musical gifts with us. My deepest gratitude to our choirs of all ages and soloists who have graciously given their time and talents for God’s glory this past year. Come, rejoice, and sing as we celebrate the gift of music in the life of our church on Music Sunday, June 2!